Book Review: “The Culture Map”

Book: The Culture Map by Erin Meyer

Reviewer: Bobby Powers

My Thoughts: 10 of 10

The Culture Map is one of the most important business books I've ever read. It's a book I could envision a CEO requiring her entire company to read. It's that good, and it's that practical. Meyer's book is hard to summarize because so much of its value comes down to the powerful stories she tells—stories that inject empathy into any international business situation a person could face. But I've done my best to recap the overarching themes below.

What I Learned from the Book

There is no "right" or "wrong" way to make decisions, give feedback, persuade someone, or disagree with a colleague. Each country around the world has different implicit and explicit norms for each of these tasks. And in fact, my home country (the U.S.) is really weird on a lot of cultural scales. We're an outlier in numerous ways, and things that may seem normal to a fellow American could seem strange to 100+ other countries around the globe.

As an international businessperson, it's important to learn the differences between each culture where you interact with co-workers, clients, and suppliers. The more you know about the history and philosophy of a country, the more effectively you can lead and communicate in that location.

As Meyer says:

"When interacting with someone from another culture, try to watch more, listen more, and speak less. Listen before you speak and learn before you act."

Selected Quotes & Ideas from the Book

Background

- "The sad truth is that the vast majority of managers who conduct business internationally have little understanding about how culture is impacting their work."

- "Unless we know how to decode other cultures and avoid easy-to-fall-into cultural traps, we are easy prey to misunderstanding, needless conflict, and ultimate failure."

- "Millions of people work in global settings while viewing everything from their own cultural perspectives and assuming that all differences, controversy, and misunderstanding are rooted in personality. This is not due to laziness. Many well-intentioned people don't educate themselves about cultural differences because they believe that if they focus on individual differences, that will be enough."

- "Unfortunately, this point of view has kept thousands of people from learning what they need to know to meet their objectives. If you go into every interaction assuming that culture doesn't matter, your default mechanism will be to view others through your own cultural lens and to judge or misjudge them accordingly."

Meyer's 8 Cultural Scales

- "I've been able to turn my classroom into a laboratory where the executive participants test, challenge, validate, and correct the findings from more than a decade of research."

- "This rich trove of information and experience informs the eight-scale model that is at the heart of this book. Each of the eight scales represents one key area that managers must be aware of, showing how cultures vary along a spectrum from one extreme to its opposite."

- "Whether you need to motivate employees, delight clients, or simply organize a conference call among members of a cross-cultural team, these eight scales will help you improve your effectiveness. By analyzing the positioning of one culture relative to another, the scales will enable you to decode how culture influences your own international collaboration and avoid painful situations."

- "The culture sets a range, and within that range each individual makes a choice. It is not a question of culture or personality, but of culture and personality."

- "Because what is important on the scale is the relative gap between two countries, someone from any country on the map can apply the book's concepts to their interactions with colleagues from any other country."

- "The point here is that, when examining how people from different cultures relate to one another, what matters is not the absolute position of either culture on the scale but rather the relative position of the two cultures. It is this relative positioning that determines how people view one another."

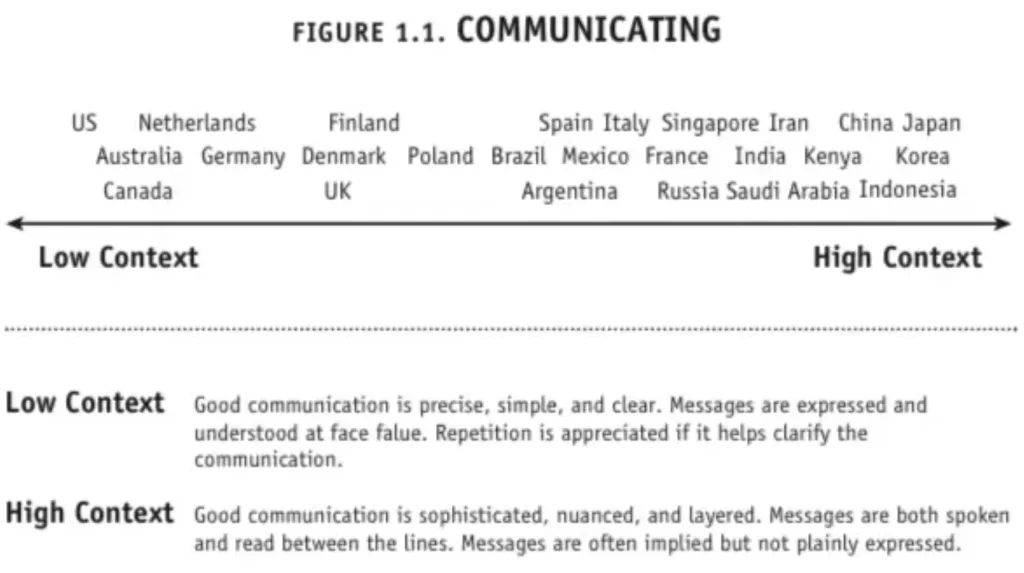

Scale #1 - Communicating: Low-Context vs. High-Context

- "The skills involved in being an effective communicator vary dramatically from one culture to another."

- "In the United States and other Anglo-Saxon cultures, people are trained (mostly subconsciously) to communicate as literally and explicitly as possible. Good communication is all about clarity and explicitness, and accountability for accurate transmission of the message is placed firmly on the communicator: 'If you don't understand, it's my fault.'"

- "By contrast, in many Asian cultures, including India, China, Japan, and Indonesia, messages are often conveyed implicitly, requiring the listener to read between the lines. Good communication is subtle, layered, and may depend on copious subtext, with responsibility for transmission of the message shared between the one sending the message and the one receiving it."

- "In a high-context culture like Iran, it's not necessary—indeed, it's often inappropriate—to spell out certain messages too explicitly."

- "Imagine what happens when two people are married for fifty or sixty years. Having shared the same context for so long, they can gather enormous amounts of information just by looking at each other's faces and gestures. Newlyweds, however, need to state their messages explicitly and repeat them frequently to ensure they are received accurately."

- "But when team members come from different cultures, high-context communication breaks down...Multicultural teams need low-context processes."

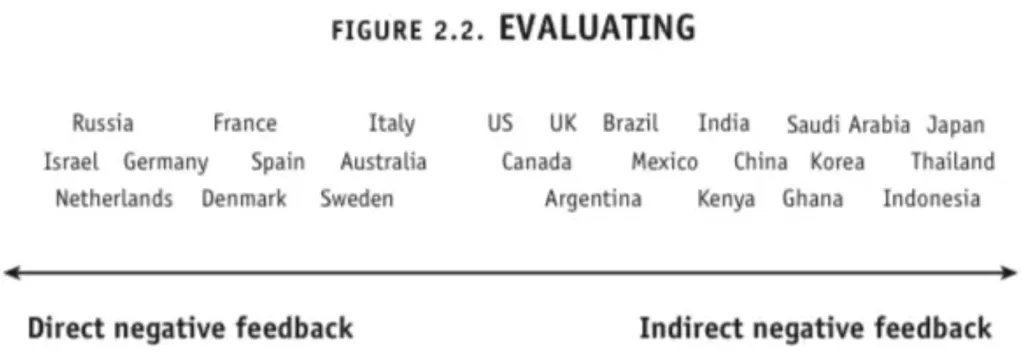

Scale #2 - Evaluating: Direct vs. Indirect Negative Feedback

- "People in all cultures believe in 'constructive criticism.' Yet what is considered constructive in one culture may be viewed as destructive in another."

- "Some cultures that are low-context and explicit may be cryptically indirect with negative criticism, while other cultures that speak between the lines may be explicit, straight talkers when telling you what you did wrong."

- "More direct cultures tend to use what linguists call upgraders, words preceding or following negative feedback that make it feel stronger, such as absolutely, totally, or strongly: 'This is absolutely inappropriate,' or 'This is totally unprofessional.'"

- "By contrast, more indirect cultures use more downgraders, words that soften criticism, such as kind of, sort of, a little, a bit, maybe, and slightly. Another type of downgrader is a deliberate understatement, a sentence that describes a feeling the speaker experiences strongly in terms that moderate the emotion—for example, saying 'We are not quite there yet' when you really mean 'This is nowhere close to complete,' or 'This is just my opinion' when you really mean 'Anyone who considers this issue will immediately agree.'"

- "The continental European cultures to the left or middle often experience Americans as strikingly indirect, while Latin Americans perceive the same Americans as blunt and brutally frank in their criticism style."

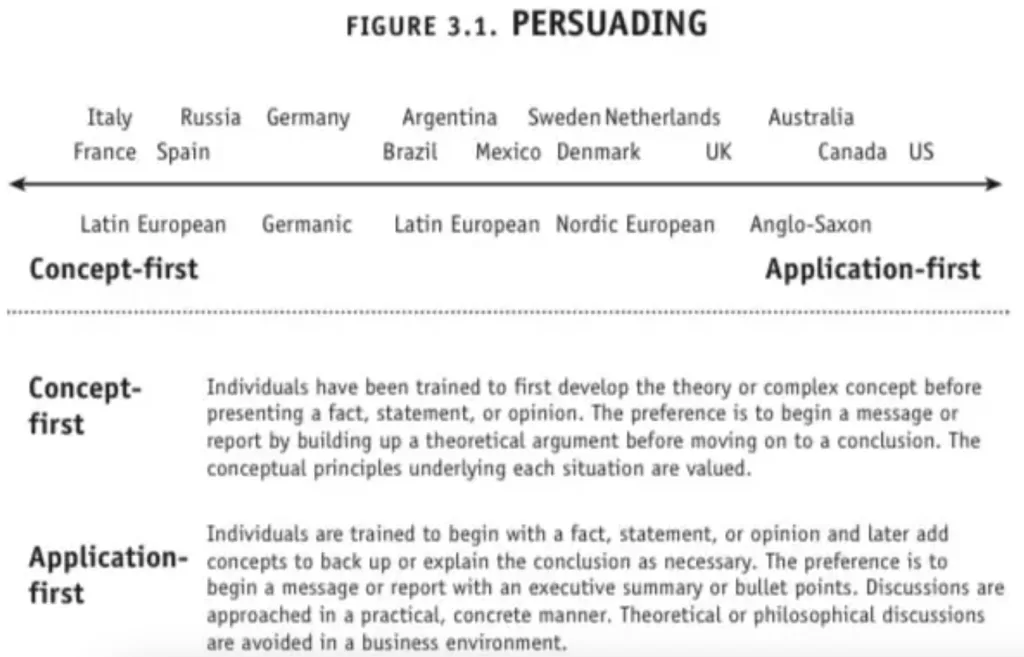

Scale #3 - Persuading: Principles-First vs. Applications-First

- "Principles-first reasoning (sometimes referred to as deductive reasoning) derives conclusions or facts from general principles or concepts."

- "On the other hand, with applications-first reasoning (sometimes called inductive reasoning), general conclusions are reached based on a pattern of factual observations from the real world...you observe data from the real world, and, based on these empirical observations, you draw broader conclusions."

- "In business, as in school, people from principles-first cultures generally want to understand the why behind their boss's request before they move to action. Meanwhile, applications-first learners tend to focus less on the why and more on the how."

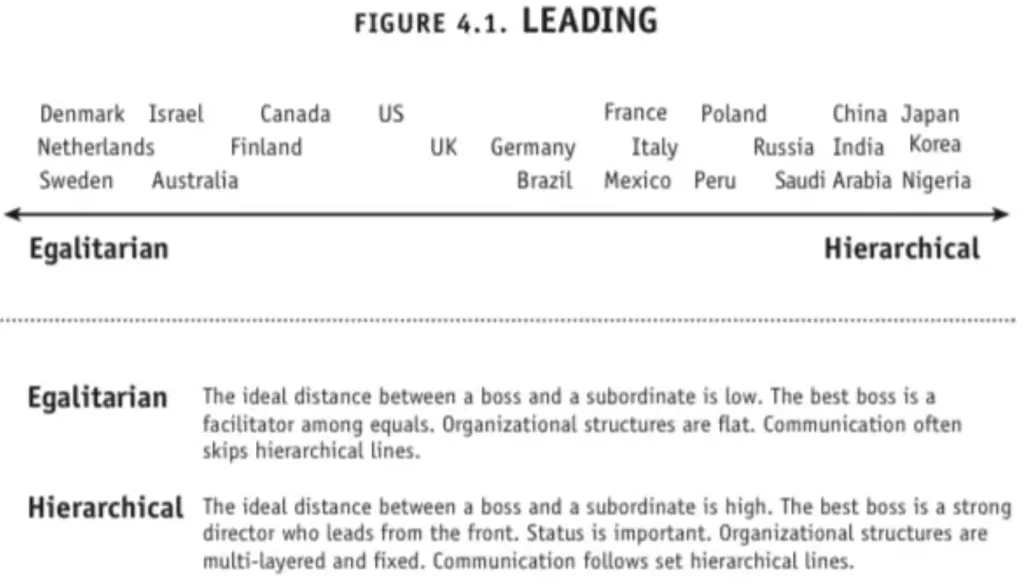

Scale #4 - Leading: Egalitarian vs. Hierarchical

- This scale is based on work from cross-cultural researcher Geert Hofstede, who "developed the term 'power distance' while analyzing 100,000 management surveys at IBM in the 1970s. He defined power distance as 'the extent to which the less powerful members of organizations accept and expect that power is distributed unequally.'"

- "The Leading scale takes Hofstede's idea of power distance and applies it specifically to business. Power distance relates to questions like:

- How much respect or deference is shown to an authority figure?

- How god-like is the boss?

- Is it acceptable to skip layers in your company? If you want to communicate a message to someone two levels above or below you, should you go through the hierarchical chain?"

- Egalitarian = Low power distance

- Hierarchical = High power distance

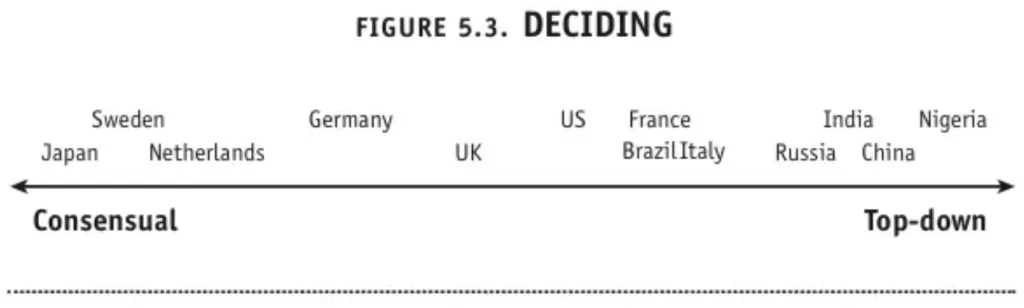

Scale #5 - Deciding: Consensual vs. Top-Down

- "In a consensual culture, the decision making may take quite a long time, since everyone is consulted. But once the decision has been made, the implementation is quite rapid, since everyone has completely bought in and the decision is fixed and inflexible—a decision with a capital D, we might say."

- "By contrast, in a top-down culture, the decision-making responsibility is invested in an individual. In this kind of culture, decisions tend to be made quickly, early in the process, by one person (likely the boss). But each decision is also flexible—a decision with a lowercase d."

- "Either of these systems can work, as long as everyone understands and follows the rules of the game. But when the two systems collide, misunderstandings, inefficiency, and frustration can occur."

- "The more both sides of the culture divide talked about it, the more natural it became for them to adjust to one another—and the more they enjoyed working together. As with so many challenges related to cross-cultural collaboration, awareness and open communication go a long way toward defusing conflict."

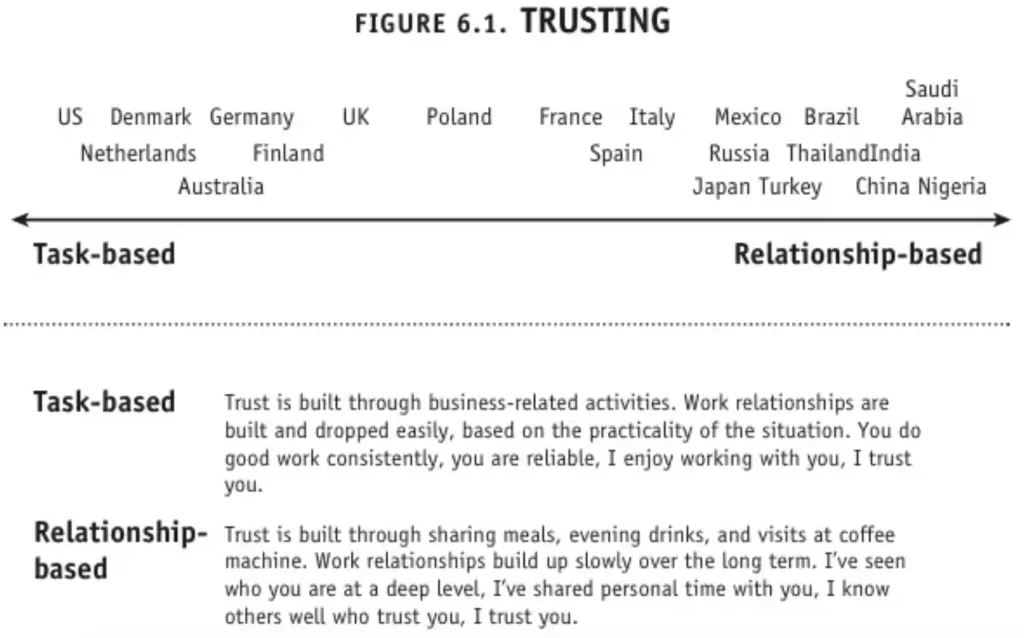

Scale #6 - Trusting: Task-Based vs. Relationship-Based

- In some cultures, trust is primarily built by completing business-related tasks together. In others, it's built by having non-work conversations and getting to know each other on a personal level (outside the workplace).

- "As a general rule, the more relationship-based the society, the more social conversation surrounds the task."

- "When working in a relationship-based culture such as Mexico, the moment you switch from boardroom to restaurant or bar is the moment you need to begin acting as if you are out on the town with your best friends. Don't worry about saying or doing the wrong thing. Be yourself—your personal self, not your business self. Dare to show that you have nothing to hide, and the trust—and likely the business—will follow."

- "American managers (task-based) make a concerted effort to ensure that personal relationships do not cloud the way they approach business interactions—in fact, they often deliberately restrict affective closeness with people they depend on for economic resources, such as budgeting or financing. After all, in countries like the United States or Switzerland, 'business is business.' In countries like China or Brazil, 'business is personal.'"

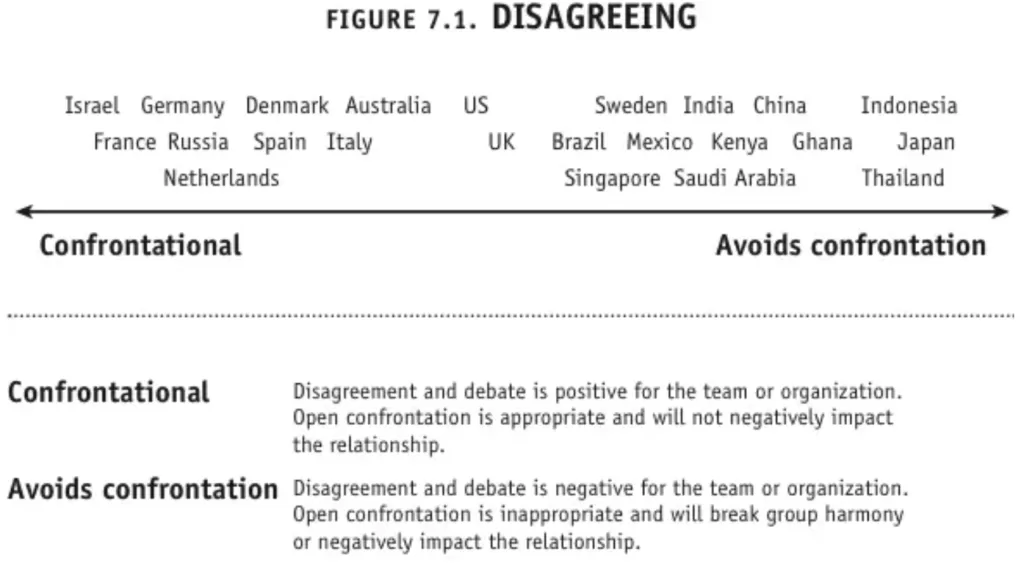

Scale #7 - Disagreeing: Confrontational vs. Avoids Confrontation

- "In Confucian societies like China, Korea, and Japan, preserving group harmony by saving face for all members of the team is of utmost importance."

- For example, "In Japanese culture, you almost never see middle management disagreeing openly with higher management or younger people disagreeing with older people. It would be viewed as disrespectful."

- In contrast, "students in the French school system (a confrontational disagreement society) are taught to reason via thesis, antithesis, and synthesis, first building up one side of the argument, then the opposite side of the argument, before coming to a conclusion. Consequently, French businesspeople intuitively conduct meetings in this fashion, viewing conflict and dissonance as bringing hidden contradictions to light and stimulating fresh thinking."

- "To begin to assess where your own culture falls on this scale, ask yourself the question, 'If someone in my culture disagrees strongly with my idea, does that suggest they are disapproving of me or just of the idea?'"

- "To place a culture on the Disagreeing scale, don't ask how emotionally people express themselves. Instead, focus on whether an open disagreement is likely to have a negative impact on the relationship."

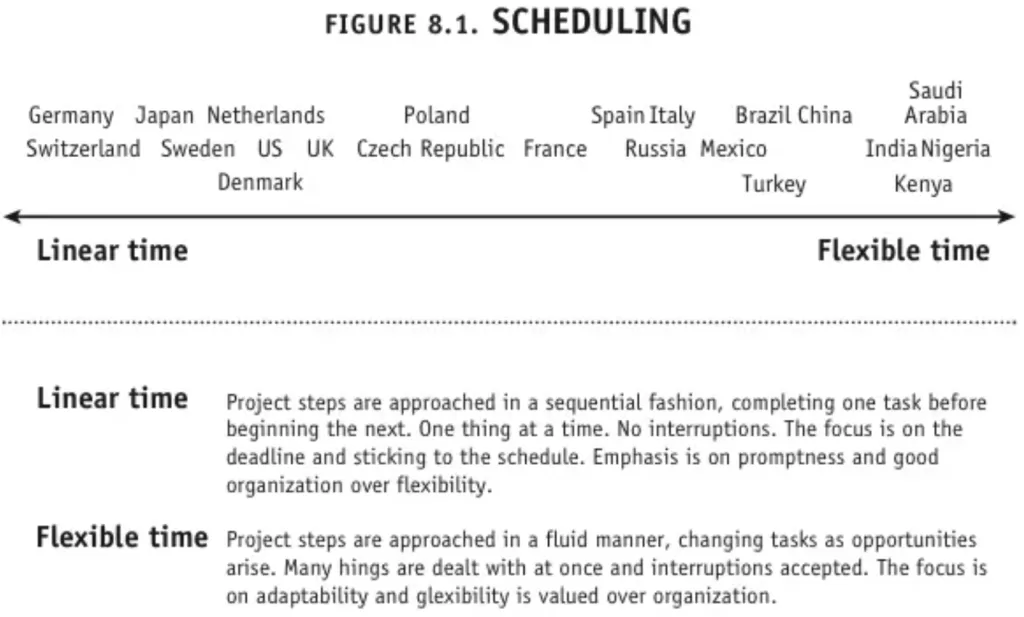

Scale #8 - Scheduling: Linear-Time vs. Flexible-Time

- "Scheduling is a state of mind that affects how you organize your day, how you run a meeting, how far you must plan in advance, and how flexible those plans are. Yet what is considered appallingly late in one culture may be acceptably on time in another."

- "If you live in Germany (a linear-time society), you probably find that things pretty much go according to plan. Trains are reliable; traffic is manageable; systems are dependable; government rules are clear and enforced more or less consistently."

- "In other societies—particularly in the developing world—life centers around the fact of constant change. As political systems shift and financial systems alter, as traffic surges and wanes, as monsoons or water shortages raise unforeseeable challenges, the successful managers are those who have developed the ability to ride out the changes with ease and flexibility."

- Linear-time cultures prioritize punctuality. Flexible-time cultures prioritize adaptability. Humorously, both ends of the spectrum think of the other side's way as inefficient.

Think you’d like this book?

Other books you may enjoy:

The Culture Code by Daniel Coyle

The Fearless Organization by Amy Edmondson

Other notable books by the author:

No Rules Rules by Reed Hastings and Erin Meyer

Want to become a stronger leader?

Sign up to get my exclusive

10-page guide for leaders and learners.