Productive Disagreement Around the Dinner Table

It’s Thanksgiving week: the official start of the holidays. Prepare for food comas, eggnog hangovers, Christmas consumerism, and contentious conversations around the turkey table.

For many, the holidays are a joyous but difficult time. Family gatherings degrade into fights about heated topics like politics and religion.

While we likely can’t avoid the tough conversations, we can at least prevent them from turning into legendary family brawls. Productive disagreement is definitely feasible.

Here are seven ideas for making conflict more constructive this holiday season:

(1) Find common ground

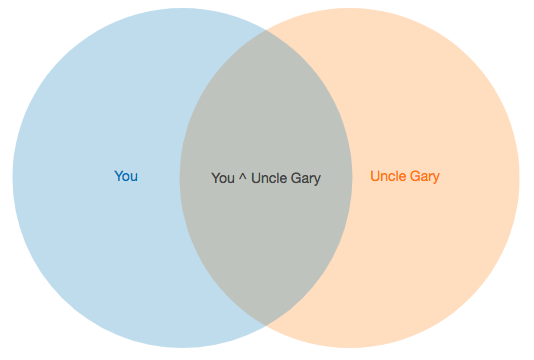

You will never find someone who agrees with all of your opinions. Similarly, you will never find someone who disagrees with all of them. There is always some opinion overlap. There is always common ground.

Maybe you are “pro-choice” and your Uncle Gary is “pro-life,” but you both love football. Knowing you share a passion for football helps you see each other as people. Common ground humanizes tough situations.

In tough conversations, your job is to find the common ground.

If Uncle Gary raises the topic of abortion after you finish talking about the Seahawks-Packers game, your first job in the abortion conversation is to find where you and Uncle Gary agree. Maybe you both believe in the sanctity of life: you are worried about the safety of the mother, while Uncle Gary is worried about the safety of the child. Voila! Your common ground is protecting life. Start there.

(2) Sit on the same side of the table to solve the problem

Once you’ve identified your common ground, use those points of agreement to align yourself on the same side of the table with the other person. You are collectively trying to solve a difficult problem.

Mentally picture yourself sitting down on the same side of the table with Uncle Gary. On the other side of the table is the problem: how our country should handle the complex issue of abortion.

You and Uncle Gary agree on a few things and you disagree on a few things. However, you’re both good people trying to solve a tough problem. Use your agreement to build on each other’s ideas, teach each other new things, and collectively work to discuss the problem on the other side of the table.

(3) Look to BUILD, not DESTROY

In every conversation, we signal our intentions with the phrases we use. If our intention is to build others up, that is obvious in our speech. Similarly, if we intend to destroy others’ arguments to make ourselves look smart, that will also be obvious.

BUILDING sounds like “Yes, and…”

- “Yes, I agree with you. Another thing to consider is…”

- “Yes, that makes a lot of sense. I’ve also been thinking about…”

- “Yes, I can see why you think that. I think about it a bit differently, and maybe you can help me see it your way…”

DESTROYING sounds like “No, that’s wrong…”

- “No, I think you’re wrong. You haven’t considered…”

- “No, that doesn’t make any sense to me.”

We can make our conversations more constructive by BUILDING on what the other person has to say rather than DESTROYING their arguments.

(4) Lead with curiosity rather than personal convictions

If your daughter states an opinion you didn’t know she held, ask her about it with genuine curiosity. Maybe she expresses a strong allegiance to President Trump, and you’ve never heard her share that before. Regardless of your personal feelings about Trump, ask meaningful questions to hear more about her opinion.

The Cambridge English Dictionary defines question as “a sentence or phrase used to find out information.” We’d be wise to remember that questions are meant to SEEK information rather than OFFER it.

Ask your questions with genuine curiosity rather than judgment. You are trying to learn, not impart wisdom. Questions should be neutral and exploratory — not biased and judgmental. Don’t “lead the witness.”

Curiosity is often expressed through tone of voice. There are no tips to provide about this; you will know it when you feel it and your daughter will know it when she hears it. Genuine curiosity shines through and builds safety in conversations.

(5) Listening is not condoning

It’s common to hear people say things like, “I couldn’t keep listening to him. I just HAD to say something.” Think about that for a minute. Really think about it. Why do we feel it is our moral imperative to speak up when we disagree with someone?

There are definitely times to speak up, but we often resort to speaking too quickly when we should instead listen. Listening to someone talk is not an act of condoning what they’re saying. Listening is an act of understanding. It is an act of selflessness. It is an act of learning.

The next time you feel a visceral reaction to something a family member says, make listening your first response. Make listening your second and third response as well. Once you’ve fully listened, then speak.

(6) Don’t paint villains into the story

It’s easy to judge others. Our creative minds paint villains and victims into every story. Sometimes our family members are the villains of those mental stories. We relish the opportunity to pull out our figurative paintbrush to adorn Aunt Carol in a black dress and a twisted smile.

Next time you hear Aunt Carol say something you deem “ridiculous,” holster your paint brush. Assume positive intent, or at least force yourself to question your preconceived notions about what kind of person would say something like what Aunt Carol just said.

Remember that each of us is formed by our experiences. If Aunt Carol says something that comes across as ignorant, uncaring, or judgmental, remind yourself that if you lived her life, you’d likely be predisposed to think the same way.

(7) Know when to walk away

Sometimes tensions escalate beyond the point of constructive dialogue. When you can tell a conversation is getting too tense, the best choice is to walk away.

Here are a few triggers that could indicate it’s time to walk:

- You feel like punching someone

- Someone deeply insulted you rather than your opinion

- You start to think you can no longer view someone as a “good person” based on what he or she just said

- Someone just turned the conversation toward one of your hot button topics and you don’t trust yourself to constructively discuss it

If you observe those triggers, politely ask to change the topic. You can even appeal to the spirit of the season: “I’d love to steer clear of this topic and just have a relaxing conversation. For me, politics don’t go well with turkey and stuffing.” If your family member doesn’t take the hint, gently excuse yourself and walk away.

Sometimes running out of a burning building is better than trying to put out the fire.

You’ll probably never get your aunt/uncle, niece/nephew, daughter/son, mom/dad, or sister/brother to change their mind about Trump, Kavanaugh, Pelosi, Mueller, abortion, gay marriage, immigration, etc. That’s okay.

Set a reasonable bar for the conversation. Changing a worldview is often an unreasonable bar. A more reasonable goal is productive disagreement and mutual respect.

Seek understanding rather than changed opinions.