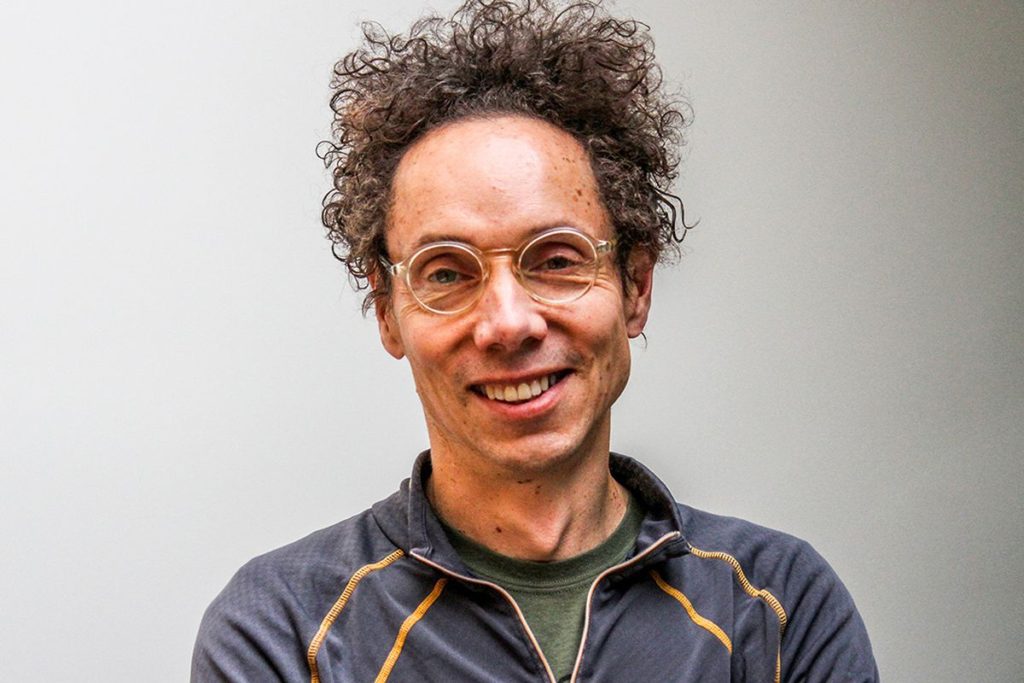

Thank You, Malcolm Gladwell

As a kid, I joined the Pizza Hut “Book It” program and read furiously to earn baseball tickets, free books, and delicious personal pan pizzas. Along the way, I acquired a love for reading itself.

I solved mysteries alongside The Hardy Boys and Encyclopedia Brown, joined Phileas Fogg in his worldwide quest, and sailed the Hispaniola with cabin boy Jim Hawkins.

Then, in high school and college, everything changed. Reading became a chore rather than a passion. Required reading and comprehension quizzes replaced pleasure reading. I rarely enjoyed what I read.

During my senior year of college, I picked up the book Blink by Malcolm Gladwell. Someone had recommended the book to me, but I’m still unsure what made me buy it. Blink was the first “non-required” book I had read in years.

Gladwell reignited my passion for reading. I realized I could learn new things AND enjoy reading at the same time, which was a revelation to me. My world re-opened.

Previously, I thought all nonfiction was boring. In my mind, nonfiction was relegated to the classroom, where it could quietly bore students who were forced to slog through passages upon which they could write opinion pieces for classroom discussion. Gladwell disproved my prior assumptions about nonfiction.

As an author, Gladwell is often criticized for his lack of academic rigor. He is a journalist (read: storyteller), not a data scientist. He simplifies ideas to their core.

As an example, Gladwell popularized the “10,000-hour rule” in his book Outliers, which is an idea that comes from the research of Anders Ericsson.

Gladwell also popularized the concept of “thin-slicing” and the notion that sometimes we can make better decisions with intuition than we can with slow, reasoned thinking. Renowned psychologist Daniel Kahneman later wrote the far more scientific work Thinking, Fast and Slow, which explained the science behind “System 1” (fast and instinctive) thinking vs. “System 2” (slow and logical) thinking.

Many authors, including Ericsson and Kahneman themselves, have lampooned Gladwell for his oversimplified analysis of concepts like the 10,000-hour rule and thin-slicing.

Academia often exhibits a contempt for those who simplify its hallowed theories and principles.

But there is extreme value in the popular press mentality of distilling an idea for the masses. Without Gladwell, I would still think that reading is boring and nonfiction is for academics. Without Gladwell, I would be spending hundreds more hours in front of my television. Without Gladwell, I would have never started my online book blog or email newsletter. Without Gladwell, I would never have aspired to become an author.

Often, the best way to articulate an idea is to simplify it. Sometimes it is necessary to sacrifice accuracy for understanding.

I think back to when my high school chemistry teacher taught our class about electrons. He told us that electrons orbit the nucleus of an atom (a concept that came from Danish physicist Neils Bohr).

Several years later, in my college chemistry course, I found out that the Bohr model was inaccurate. Electrons exist in a “cloud,” and it is impossible to predict where an electron is at any point in time. This “electron cloud model” had replaced the old Bohr model decades before I entered high school.

I remember sitting in my college chemistry class with the distinct feeling that I had been lied to in high school. Why would my teacher explain a concept that was known to be false?

Eventually, I came to terms with the fact that a group of 16-year-olds who were barely old enough to drive would be able to better understand the old Neils Bohr model than the far more confusing electron cloud model.

My high school teacher had sacrificed a bit of accuracy for understanding, and I think he made the right choice.

Often, the best way to teach (or popularize) a concept is to explain it through an analogy or metaphor to something your audience already understands. Find a way to simplify the concept, then gradually build upon that foundation and fill in the gaps to complete the picture. Or better yet, leave the last ten percent of the explanation to the scientists who can explain the rest in a scholarly journal.

Personally, I’m indebted to the hard work of brilliant storytellers like Malcolm Gladwell. Thank you for making me interested enough in nonfiction to not only read your work, but also seek out other research to dive deeper and further expand my knowledge.