Strunk & White’s Top 13 Writing Tips

When I began asking people for book recommendations on the art of writing, one book came up more than any other: The Elements of Style by William Strunk Jr. and E. B. White.

E. B. White wrote the children’s classics Charlotte’s Web, Stuart Little, and The Trumpet of the Swan. But before his writing career began, White was a student in William Strunk’s writing class at Cornell University. Strunk used his own 43-page writing manual to teach students proper grammar, prose, and punctuation.

After Strunk’s death, Macmillan Publishing commissioned White to revise and expand Strunk’s manual for a wider audience. The result was the lithe, 100-page book The Elements of Style.

The tiny book made a big splash with writers, selling over ten million copies and crowning Strunk and White as the dynamic duo of the writing world.

Here are the top 13 lessons I learned from The Elements of Style:

1. First, learn the rules

“It is an old observation that the best writers sometimes disregard the rules of rhetoric. When they do so, however, the reader will usually find in the sentence some compensating merit, attained at the cost of the violation. Unless he is certain of doing as well, he will probably do best to follow the rules.” -William Strunk Jr.

Young writers love to break the rules. They hide behind the excuse that they’re “blazing their own trail,” playing with the rules of grammar and punctuation just like they’ve seen their favorite authors do. If Cormac McCarthy and e.e. cummings can get away with it, why can’t I?

Well, because you aren’t McCarthy or cummings — at least not yet. They learned the rules before breaking the rules, and so should you.

What most writers don’t understand is that readers can tell whether you’re breaking the rules out of ignorance or ingenuity. If a writer uses a few fragments, it’s easy to discern whether they’re doing that because they don’t know how to form a complete sentence or because they think using a fragment is a more impactful way of conveying that particular idea.

Readers know the truth; you cannot fool them. Take the time to learn the rules before breaking the rules.

2. Make nouns and verbs do the heavy lifting

“Write with nouns and verbs, not with adjectives and adverbs. The adjective hasn’t been built that can pull a weak or inaccurate noun out of a tight place. This is not to disparage adjectives and adverbs; they are indispensable parts of speech…however, it is nouns and verbs, not their assistants, that give good writing its toughness and color.” -Strunk & White

Legendary writers do much with little. If you read authors like Ernest Hemingway, Raymond Chandler, and Margaret Atwood, you’ll notice they choose the perfect verb to convey the emotion of each situation.

Their characters don’t cry loudly, they weep.

They don’t walk quietly, they creep.

They don’t talk softly, they whisper.

The verbs do the work. A well-chosen verb can put two or three adverbs on the unemployment line.

Great authors also know how to weaponize their nouns. They pick specific, concrete nouns that convey all of the information the reader needs to know.

3. Cut the deadwood from your writing

“Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences…This requires not that the writer make all sentences short, or avoid all detail and treat subjects only in outline, but that every word tell.” -Strunk & White

Strong writing is lean. Unfortunately, society has often rewarded bloated writing. In school, students are forced to reach a certain page count or word count. In freelancing, many writers are paid by the word. These experiences have instilled poor habits, prompting authors to say more rather than less.

Here are a few examples of bloated writing compared to lean writing:

- “There is no doubt that” → “Doubtless”

- “This is a subject that” → “This subject”

- “He is a man who” → “He”

- “The fact that” → “Because” or “Since”

Omit unnecessary words. Every word should earn its keep.

4. Use repetition to strengthen your writing

“Express coordinate ideas in similar form. This principle, that of parallel construction, requires that expressions similar in content and function be outwardly similar…The familiar Beatitudes exemplify the virtue of parallel construction:

Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are they that mourn: for they shall be comforted.

Blessed are the meek: for they shall inherit the earth.

Blessed are they which do hunger and thirst after righteousness: for they shall be filled.

The unskilled writer often violates this principle, mistakenly believing in the value of constantly varying the form of expression.” -Strunk & White

When I was in high school and college, I tried to vary my word choice as much as possible. I saw it as a failure if I had to repeat the same word or phrase.

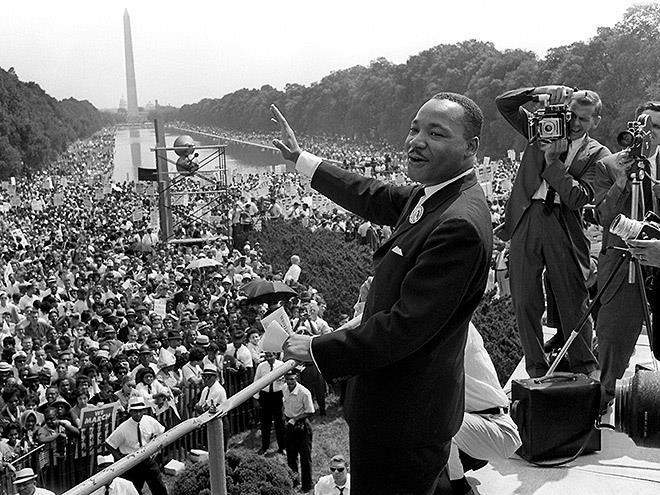

Then I noticed that some of the most memorable books and speeches throughout history contained intentional repetition. Consider Martin Luther King Jr’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

Selectively repeating a word or phrase is a powerful communication device. (There’s even a name for it: anaphora.) Rather than avoiding repetition, selectively use anaphora to make your prose more poetic and memorable.

5. Keep related words together

“The position of words in a sentence is the principal means of showing their relationship. Confusion and ambiguity result when words are badly placed.” -Strunk & White

Strunk and White provide a hilarious example to demonstrate the importance of word placement. Read this sentence: “New York’s first commercial human-sperm bank opened Friday with semen samples from eighteen men frozen in a stainless steel tank.”

Are the samples frozen or do we need to worry about those poor eighteen guys who are now ice cubes?

Word placement matters. To avoid ambiguity, put your modifiers (like adjectives and prepositional phrases) close to the words they’re describing.

6. Do not overstate your point

“When you overstate, readers will be instantly on guard, and everything that has preceded your overstatement as well as everything that follows it will be suspect in their minds because they have lost confidence in your judgment or your poise. Overstatement is one of the common faults. A single overstatement, wherever or however it occurs, diminishes the whole, and a single carefree superlative has the power to destroy, for readers, the object of your enthusiasm.” -Strunk & White

When I first started writing, I believed that the best way to emphasize a point was to add words like “brilliant,” “very,” “highly,” etc. It took me months to realize that one of the easiest ways to weaken your argument is by trying to strengthen it with cheap words.

Here are a few examples of words and phrases that don’t help as much as you may think:

- “To be honest…” or “honestly…”

- “Extremely” or “terribly”

- “Best” or “worst”

This rule is closely related to the adage “show, don’t tell.” Rather than using an adjective or adverb to try to convince your reader of something, give them a story, example, or dialogue that demonstrates the point. You shouldn’t need to convince anyone of anything; the story itself should do the heavy lifting.

One of the easiest ways to weaken your argument is by trying to strengthen it with cheap words.

7. Write with confidence

“Rather, very, little, pretty — these are the leeches that infest the pond of prose, sucking the blood of words.” -Strunk & White

In the same way that you should avoid overstating your point, you should also avoid understating it. It’s easy to fall into the trap of hedging your writing with qualifying words.

Readers know that advice articles and op-eds are opinion pieces. You don’t need to rub your insecurity in their face.

Qualifiers are quicksand for new writers — especially young advice writers. Advice writers don’t want to steer anyone in the wrong direction, so they sometimes soften their recommendations with language like “I think,” “maybe,” or “this seems to be the case.”

Readers know that advice articles and op-eds are opinion pieces. You don’t need to rub your insecurity in their face. Speak confidently. Represent your ideas fairly and accurately, but don’t couch every sentence in self-doubt.

8. Place yourself in the background

“Write in a way that draws the reader’s attention to the sense and substance of the writing, rather than to the mood and temper of the author…Therefore, the first piece of advice is this: to achieve style, begin by affecting none — that is, place yourself in the background.” -Strunk & White

The reader’s entire focus should be on the story — not the person who wrote the story. You are not the story.

Don’t use big words, complex explanations, or overly technical language because those things inhibit the reader’s ability to understand the story.

Author Steven Pinker says, “Classic prose is a pleasant illusion, like losing yourself in a play.” Allow the reader to get lost in the play.

9. Focus on simplicity and sincerity over style

“Young writers often suppose that style is a garnish for the meat of prose, a sauce by which a dull dish is made palatable. Style has no such separate entity; it is nondetachable, unfilterable. The beginner should approach style warily, realizing that it is an expression of self, and should turn resolutely away from all devices that are popularly believed to indicate style — all mannerisms, tricks, adornments. The approach to style is by way of plainness, simplicity, orderliness, sincerity.” -Strunk & White

New writers often bemoan that they haven’t yet “found their voice.” They want to sound cool and tough like Raymond Chandler, heavy and cerebral like James Joyce, or youthful and whimsical like J.K. Rowling. But it’s impossible to know your style if you’ve barely published anything.

“As you become proficient in the use of language, your style will emerge, because you yourself will emerge,” Strunk and White advise.

Stop focusing on style. For now, worry about making your writing clear and concise. Style will follow; you just need to be patient.

10. Organize your thoughts for the reader

“Writing, to be effective, must follow closely the thoughts of the writer, but not necessarily in the order in which those thoughts occur.” -Strunk & White

One of the toughest aspects of rewriting is cleaning your mental slate in order to see your words as the reader will see them. The best writers are able to notice when their work is irrational or incoherent. When they notice those flaws, they fix the logical progression of their story.

Here are a few logical progressions you can use:

- Introductory story that illustrates a problem → Broader description of the problem → Potential solutions → Recommended solution

- Introductory story → Point #1 → Supporting material for Point #1 → Point #2 → Supporting material for Point #2 → […] → Conclusion

- Personal story → What you learned in that situation → How that lesson applies to others → Takeaway or call to action

It’s difficult to view your own writing with fresh eyes, which is one reason why editors are useful. However, it is possible to gradually learn how to see your work from the reader’s perspective.

After you’ve finished writing your entire piece, do a brief brain flush, put on your eyeglasses of ignorance, and begin reading your piece anew. As you do so, ask yourself, “As a reader, would I know what this means? Would this make sense to me?”

11. Experiment with large rewrites

“Revising is part of writing. Few writers are so expert that they can produce what they are after on the first try…Above all, do not be afraid to experiment with what you have written. Save both the original and the revised versions; you can always use the computer to restore the manuscript to its original condition, should that course seem best. Remember, it is no sign of weakness or defeat that your manuscript ends up in need of major surgery. This is a common occurrence in all writing, and among the best writers.” -Strunk & White

I’m constantly amazed by how long the editing and rewriting process takes. I often spend as much time editing my stories as I spend writing them.

Occasionally, I’ll finish writing something and realize that I only need to do some light pruning and reshaping around the edges of the story.

Other times, I will finish my first draft, then realize I need to make substantial changes. Perhaps I need to chop off entire branches of the story and graft in other branches to replace them. Or I may realize that my point doesn’t logically progress the way I intended, so I need to find new stories, facts, and quotes to connect point A to point B.

If you want to write anything worth reading, mentally prepare to spend a lot of time in “post-production.” Writing may be the fun part, but editing will pay the bills.

12. Use paragraph breaks to help your readers

“In general, remember that paragraphing calls for a good eye as well as a logical mind. Enormous blocks of print look formidable to readers, who are often reluctant to tackle them. Therefore, breaking long paragraphs in two, even if it is not necessary to do so for sense, meaning, or logical development, is often a visual help. But remember, too, that firing off many short paragraphs in quick succession can be distracting.” -Strunk & White

It’s more important now than ever before to insert frequent paragraph breaks. Why? Three reasons:

- Low attention spans: In our fast-paced society, attention spans are lower than ever, which means readers tap out faster if they lose interest.

- TONS of content: The age of the internet has turned everyone into a content creator, so readers have many other options if they get overwhelmed or lost while reading.

- Digital devices: More and more people are reading on phones and tablets with tiny screens that don’t cater well to large blocks of text.

Short paragraphs are especially useful for emphasizing key points or pithy sayings. Use longer paragraphs whenever you’re making an argument and you need points X, Y, and Z to all run in close succession.

13. Be bold. Try new things.

“Who can confidently say what ignites a certain combination of words, causing them to explode in the mind?…There is no satisfactory explanation of style, no infallible guide to good writing, no assurance that a person who thinks clearly will be able to write clearly, no key that unlocks the door, no inflexible rule by which writers may shape their course. Writers will often find themselves steering by stars that are disturbingly in motion.” -Strunk & White

Toward the end of Strunk and White’s writing rulebook, the authors throw back the curtain to say that style is arbitrary. It’s impossible to objectively separate good writing from bad writing. There is no formula: there is only what works and what doesn’t. Discerning the difference between the two takes practice and experimentation.

Much of writing is learning how to tune your ear to the frequency of what good writing sounds like. Keep working to refine your writer’s ear by experimenting with new things, reading the work of other great writers, and writing as much as you can.

If these tips were helpful, pick up a copy of The Elements of Style. It’s a great resource for any writer.

Happy writing!