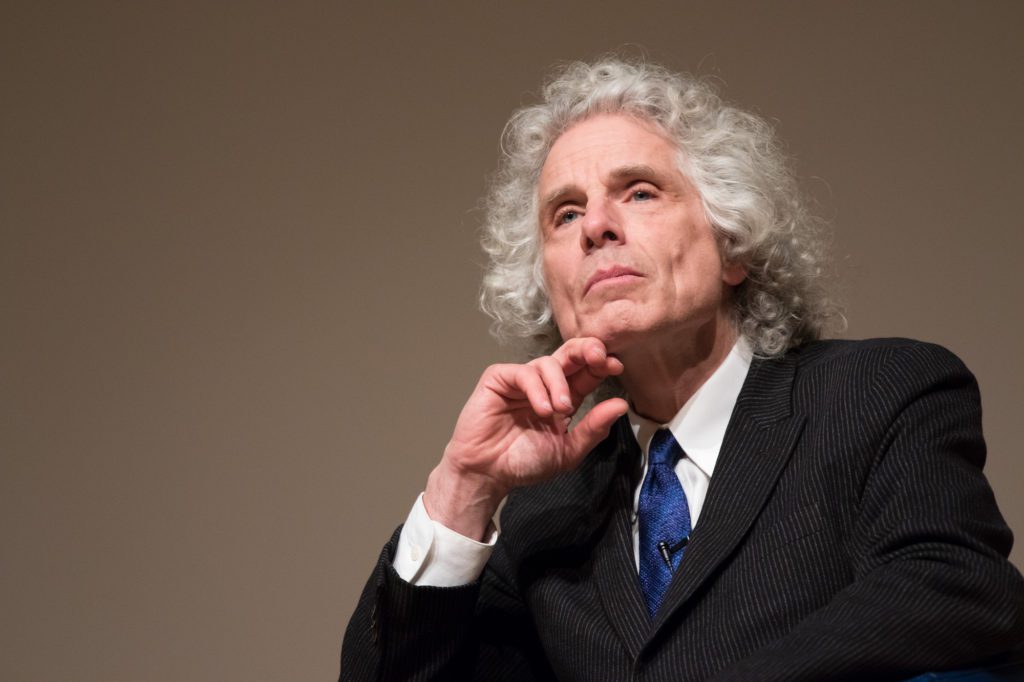

Steven Pinker’s Top 13 Writing Tips

Steven Pinker wrote the most underrated writing advice book of the past decade: The Sense of Style.

I’ve never heard another writer mention this book, which is shocking because Pinker is a titan in the world of nonfiction and The Sense of Style is one of the most effective craft books ever written.

Pinker offers hundreds of practical examples, walking through text snippets from the popular press, media, and academia to contrast strong versus weak writing.

Here are the top 13 things I learned from Pinker’s book:

1. When sensible, break the rules

“Many style manuals treat traditional rules of usage the way fundamentalists treat the Ten Commandments: as unerring laws chiseled in sapphire for mortals to obey or risk eternal damnation….Although some of the rules can make prose better, many of them make it worse, and writers are better off flouting them.” -Steven Pinker

Grammatical rules exist to make writing simpler and easier to read. But those rules sometimes produce the exact opposite: stodgy writing that isn’t relatable or engaging.

Here are a few examples, including two that we’ll unpack later in this article:

- Starting sentences with conjunctions

- Ending sentences with prepositions

- Using fragments

- Splitting infinitives

The highest aspiration of a writer should be to write words that are clear and concise. Rules shouldn’t get in the way. Flout the rules if they’re not serving you and your readers.

2. Don’t be afraid of passive voice

“Linguistic research has shown that the passive construction has a number of indispensable functions because of the way it engages a reader’s attention and memory. A skilled writer should know what those functions are and push back against copy editors who, under the influence of grammatically naïve style guides, blue-pencil every passive construction they spot into an active one.” -Steven Pinker

Ahh yes, another dictum that you’ll hear from every English teacher: avoid the passive voice. This is another rule that makes sense 90 percent of the time, but not all of the time.

When should a writer use the passive voice?

- When you don’t want to mention the agent of the action

“Caesar was killed” works better than “Brutus killed Caesar” if you don’t want to reveal the murderer yet. - When you want to keep the attention on a single character

“[T]he passive allows the writer to direct the reader’s gaze, like a cinematographer choosing the best camera angle,” says Pinker. “Actives and passives differ in which character gets to be the subject, and hence which starts out in the reader’s mental spotlight.” - When you want to portray a character’s helplessness

“Teddy was sent to the corner” shows that poor young Teddy doesn’t have much agency in the situation. - Any other time you think it will serve your story

You are the ultimate authority on what will work best in your story. Use active voice for most sentences, but don’t be afraid to use passive if you think it’s more effective in a given situation.

3. Embrace modern language

“[T]he orthodox stylebooks are ill equipped to deal with an inescapable fact about language: it changes over time. Language is not a protocol legislated by an authority but rather a wiki that pools the contributions of millions of writers and speakers, who ceaselessly bend the language to their needs and who inexorably age, die, and get replaced by their children, who adapt the language in turn.” -Steven Pinker

In their oft-referenced writing stylebook, William Strunk Jr. and E. B. White go on a tirade against writers who turn nouns into verbs (personalize, finalize, host, etc.). They thought such concoctions perverted the English language.

Pinker disagrees, saying that “every generation believes that the kids today are degrading the language and taking civilization down with it.” He argues that as the world changes, our language should change as well.

People often begin using a word or phrase because it makes sense. It somehow shortens the path from A to B. For example, Shakespeare supposedly coined the term bedroom, Dickens gave us boredom, and Twain introduced hard-boiled. All of these terms made sense, so they stuck. The same thing happened with many verbs that have been noun-ified: claim, debut, chair, etc.

Don’t be a literary snob. Write in the language of the people.

4. Make the reader feel smart

“Classic writing, with its assumption of equality between writer and reader, makes the reader feel like a genius. Bad writing makes the reader feel like a dunce.” -Steven Pinker

Pinker says good writing is a clear window that readers peer through to watch the action unfold. The fancier the words, the foggier the window.

The best writers are so good you don’t even know they’re there. The writer fades into the background because you’re not stumbling over their words.

Think about the types of words that tend to make readers stumble: foreign words (c’est la vie), long words (parsimonious), medical words (myocardial infarction), and words that people don’t commonly say aloud (bibliophile).

Avoid words like those. Substitute simpler words or phrases that adequately relay the concept, such as that’s life, frugal, heart attack, and book lover.

5. Write with confidence

“And then there’s compulsive hedging. Many writers cushion their prose with wads of fluff that imply that they are not willing to stand behind what they are saying, including almost, apparently, comparatively, fairly, in part, nearly, partially, predominately, presumably, rather, relatively, seemingly, so to speak, somewhat, sort of, to a certain degree, to some extent...” -Steven Pinker

If you’re a new writer, you will struggle to write with confidence. Your uncertainty will bleed onto the page with hedging words.

Maybe you feel that softening your argument is more transparent, honest, or vulnerable. But you must remember that readers come to you to hear your opinion. They know they’re getting your version of the story.

Share your story with confidence. Give the people what they came for: a view into what you think about something.

6. Avoid intensifiers

“Paradoxically, intensifiers like very, highly, and extremely also work like hedges. They not only fuzz up a writer’s prose but can undermine his intent…As soon as you add an intensifier, you’re turning an all-or-none dichotomy into a graduated scale. True, you’re trying to place your subject high on the scale — say, an 8.7 out of 10 — but it would have been better if the reader were not considering his relative degree of honesty in the first place.” -Steven Pinker

This one has been tough for me. I’m an excitable person, so I commonly say words like amazing, awesome, extremely, and very. But if I loaded every paragraph with intensifiers like that, my readers would have to trudge through a lot of muck to unearth the point I’m trying to make.

Pinker reminds us that intensifiers often weaken the point rather than strengthen it. Example: which of these sentences sounds more persuasive?

- “Honestly, I think people should invest more time in reading.”

- “It’s worth the time to develop a reading habit.”

Counterintuitively, by mentioning honesty in the first sentence, you draw attention to the truthfulness of your argument — making the reader less inclined to believe you! It’s much better to just come out and say whatever you want to say. No hedges. No intensifiers.

7. Choose concrete over abstract

“Could you recognize a ‘level’ or a ‘perspective’ if you met one on the street? Could you point it out to someone else? What about an approach, an assumption, a concept, a condition, a context, a framework, an issue, a model, a process, a range, a role, a strategy, a tendency, or a variable? These are metaconcepts: concepts about concepts. They serve as a kind of packing material in which academics, bureaucrats, and corporate mouthpieces clad their subject matter. Only when the packaging is hacked away does the object come into view.” -Steven Pinker

Many people make a career out of sounding smart. From lawyers to professors, marketers to politicians, abstract terminology dresses up weak arguments in fancy clothes.

“The phrase on the aspirational level adds nothing to aspire, nor is a prejudice reduction model any more sophisticated than reducing prejudice,” says Pinker.

As a writer, it’s your job to make things easier to understand — not harder. Whenever possible, use concrete terms rather than abstractions. Paint vivid pictures that your audience can read with their mind’s eye.

8. Utilize strong verbs — not zombie nouns

“Together with verbal coffins like model and level in which writers entomb their actors and actions, the English language provides them with a dangerous weapon called nominalization: making something into a noun. The nominalization rule takes a perfectly spry verb and embalms it into a lifeless noun by adding a suffix like -ance, -ment, -ation, or -ing. Instead of affirming an idea, you effect its affirmation; rather than postponing something, you implement a postponement. The writing scholar Helen Sword calls them zombie nouns because they lumber across the scene without a conscious agent directing their motion.” -Steven Pinker

While Pinker is okay with occasionally turning nouns into verbs (as mentioned in tip #3 above), he objects to most situations in which a writer would turn a verb into a noun. Verbs are the most powerful parts of speech because they get to perform the action. Don’t take the action away from them.

When you convert a verb into a noun, you turn the verb into a passive participant — immediately weakening your sentence:

- “She allotted $1 million from her estate to each child” becomes “She gave each child a $1 million allotment from her estate.”

- “He graduates in June” becomes “His graduation is in June.”

The second version contains a zombie noun that murders the sentence, whereas the first version contains a strong action verb.

Decapitate your zombie nouns; choose strong verbs instead.

9. Beware the curse of knowledge

“The curse of knowledge is the single best explanation I know of why good people write bad prose.” -Steven Pinker

Once you know something, it’s easy to forget what it was like to not know it. Your own depth of knowledge can inhibit you from articulating concepts in a simple way.

To overcome the curse of knowledge, begin with the 30,000-foot view of the topic: what is it and why should people care about it? Rather than jumping into the complex nuances of a technical topic right away, start in the shallow end of the pool, then gradually lead your readers into the deep end.

Break complex ideas down into smaller chunks. Avoid industry jargon, undefined acronyms, and unexplained assumptions. Use analogies and metaphors whenever possible to explain topics in terms your audience will understand.

10. Pare your argument down to its essentials

“It takes cognitive toil and literary dexterity to pare an argument to its essentials, narrate it in an orderly sequence, and illustrate it with analogies that are both familiar and accurate. As Dolly Parton said, ‘You wouldn’t believe how much it costs to look this cheap.’” -Steven Pinker

I often get the chance to read and edit the work of other writers. One of the most common mistakes I see in beginners’ work is that they try to do too much in a single article. Rather than saying ONE thing (and saying it well), they say 100 things (and say them poorly).

For example, let’s say you want to write about a new editing process you’ve been using that has worked well for you. Your entire story should be focused on editing — not on any other part of the writing process. Don’t go off-roading to talk about how you develop characters, what music you listen to when you write, or how to generate ideas for more stories. Stay on the path. Those other topics are interesting, but they’ll also be interesting tomorrow — in a DIFFERENT story.

11. Clean up the mess so others don’t see it

“The goal of classic style is to make it seem as if the writer’s thoughts were fully formed before he clothed them in words. As with the celebrity chef in the immaculate television kitchen who pulls a perfect soufflé out of the oven in the show’s final minute, the messy work has been done beforehand and behind the scenes.” -Steven Pinker

Writing is a messy process. Your job is to get your hands dirty — covered with misplaced modifiers and troublesome tangents— then clean up the mess so no reader would ever guess it was there.

Think of writing like throwing a house party. You want your creative process to be wild and inventive. Make a mess. Have fun. You need a little bit of crazy in the creative process. But after the party is over, you must clean up the mess you’ve made. That’s called editing. During editing, you throw out everything that doesn’t belong. Kick the tangents off your couch. Dump the garbage grammar. Straighten up to make sure everything is in its rightful place.

The clean-up process — when done well — takes a TON of work. But it’s always worth it.

12. End sentences with prepositions if you want to

“As with split infinitives, the prohibition against clause-final prepositions is considered a superstition even by the language mavens, and it persists only among know-it-alls who have never opened a dictionary or style manual to check. There is nothing, repeat nothing, wrong with Who are you looking at? or The better to see you with or We are such stuff as dreams are made on or It’s you she’s thinking of.” -Steven Pinker

Alright, alright, you caught me. I added a preposition at the end of this tip, and the sentence would have been stronger without it. Most sentences are better served by ending with a noun or verb, but Pinker says there’s nothing wrong with ending a sentence with a preposition if it makes sense to do so.

Writing should often mirror speech. It’s common to hear spoken sentences like “Who did you talk to?” Aside from catering to the literary snobs, there’s no reason to reconstruct that sentence. Any other construction would weaken the sentence and make it sound less like common speech.

13. And it’s OK to begin sentences with conjunctions

“Teachers need a simple way to teach [children] how to break sentences, so they tell them that sentences beginning with and and other conjunctions are ungrammatical. Whatever the pedagogical merits may be of feeding children misinformation, it is inappropriate for adults. There is nothing wrong with beginning a sentence with a coordinator.” -Steven Pinker

I’m thankful to the English teachers who taught me how to write, but some of their advice didn’t translate well to professional writing. For years, I refused to begin sentences with words like and, but, or, and because. Now those are some of my favorite words for kicking off sentences because they connect my last idea to my next one.

But can be used to quickly contrast one idea with another. And builds off the last concept by adding new information. Or often introduces a short alternative to something previously mentioned.

Follow Pinker’s lead: disobey your high school English teacher. If you think a conjunction is the best way to begin a sentence, then use a conjunction.

If you enjoyed these tips, check out Pinker’s book The Sense of Style.

Happy writing!