Rules for Living: How to Create the Life You’re Meant to Live

Many things in life come with instructions or operating manuals, even products that don’t seem to need them:

- Toasters (“Plug in. Insert bread. Bread becomes toast.”)

- Tamagotchi pets (“Hatch cute life form. Realize that child care is hard. Allow cute life form to die.”)

- Tanning lotion (“Apply to skin. Burn, but not too badly. Look sexy.”)

And even though many ridiculous things come with instructions, we’re not given an operating manual for the most important aspects of life — things like getting a job, finding love, saving for retirement, or becoming a decent human.

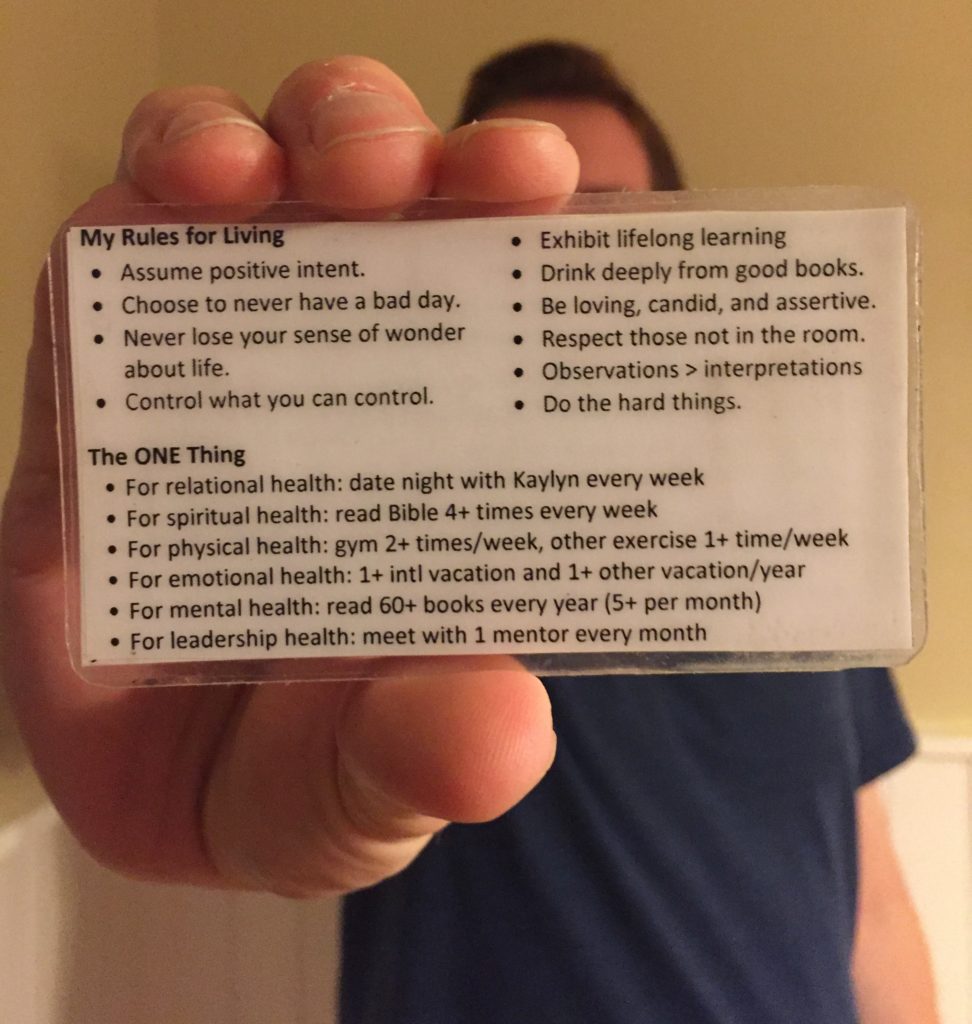

About six years ago, after repeating many life mistakes, I decided to begin writing down my own “rules for living” to serve as an operating manual for my life. I’ve been updating and editing these rules ever since.

My rules began as a notecard that I laminated and took with me in my pocket everywhere I went. Here’s an early version, with the rules across the top and one personal goal in each area of my life along the bottom:

Then my rules outgrew the card, so I began keeping them in my journal. And now, those rules are seeing the bright lights of cyberspace for the first time.

Well…sorta the first time. You see, when you have rules for life, they tend to show up everywhere. Avid followers of mine will notice fingerprints from these rules in many of the stories I’ve written the past several years. These themes truly do guide my life.

And while there is zero chance that every one of these rules will apply to your life, I’ve found that reading someone else’s operating manual can sometimes offer glimpses into what rules should show up in your own manual.

For example, I’ve enjoyed reading other people’s rules for life — like Ray Dalio’s Principles and John Wooden’s A Game Plan for Life. Every biography or memoir has the potential to add chapters and verses to your own operating manual.

So without further ado, here are the operating rules that guide my life.

1.0 — Completely own who you are

“There’s no force more powerful than someone completely owning who they are.” -James Pratt

My friend and former boss texted me the above quote as I headed into a meeting. I was preparing to give some very difficult feedback to someone who held my career in their hands, and I was super nervous.

I had been trying to decide if it was worth it. Should I really speak my opinion? Why bother going out on a limb? Couldn’t I just keep my head down and shut up?

Then I received that text and realized that silence wasn’t true to who I was. I had to completely own who I was and what I believed was right. So I decided to give the feedback.

The result: I shared a difficult message that needed to be shared, and it made a profound impact on our business. As a bonus, my small act of courage greased the skids for future acts of courage and self-confidence in my life.

1.1 — Don’t hide your passions

“What makes you different or weird, that’s your strength.” -Meryl Streep

In high school, I was cut from the basketball team three years in a row. Three years of practicing during the entire off-season. Three years of running suicide drills at tryouts. Three years of excitedly waiting for the team roster to get posted. Three years of not finding my name on the roster.

It was painful. And the most painful part of it wasn’t the blow to my pride (although that did suck) — it was that I genuinely LOVE to play basketball. Getting cut meant I wouldn’t get to play as much of the sport I loved.

But after every year’s tryouts, after that roster got posted on the wall without the name Bobby Powers, I continued to look for any possible opportunity to play basketball. I practiced for hours by myself, coaxed friends into playing with me at lunch, and organized pick-up games.

A couple of times, classmates made fun of me for wanting to play all the time. They thought it was silly that a guy who got cut from the team was still so passionate about the sport. They seemed to believe that a person’s ability should always exceed their passion: It was cool to be a star player who didn’t care, but it was lame to be a wannabe who did care.

As I noticed my classmates’ reactions to my enthusiasm, I questioned whether to hide my passion. I realized that it would be easier to act like I didn’t care.

“We must risk delight. We must have the stubbornness to accept our gladness in the ruthless furnace of this world.” -Jack Gilbert

But I decided to “risk delight” despite the fact that others would judge me for it. And even though that situation happened way back in high school, the lesson still applies today. Similar situations have arisen with other interests of mine throughout the years: bands, books, clothes, hobbies, etc.

Deciding to follow my passions rather than hiding them is a decision I must make anew every day. My goal is to continue to risk delight.

1.2— Never lose your childlike sense of wonder about life

“Listen to your life. See it for the fathomless mystery that it is. In the boredom and pain of it no less than in the excitement and gladness: touch, taste, smell your way to the holy and hidden heart of it because in the last analysis all moments are key moments, and life itself is grace.” -Frederick Buechner

One of the biggest insults you can levy against someone is to say they’re acting like a child. Kids get a bad rap.

Screw that. I think all of us need to be more childlike.

Have you ever sat and watched the way children interact with the world around them? They’re inquisitive, excited, hopeful, and utterly full of delight. They view the world as a magical, wild, and powerful thing.

They run through sprinklers, pick up rocks to search for creepy crawlies, ask old people how trees grow, and view every snowfall as a chance to resurrect last year’s Frosty.

Damn, we need more of that. Too many of us are chained to our desks, perpetually busy and frazzled. Or our eyeballs are cemented to our phones, neglecting everything around us in the real world because we’re too busy scoring hits of dopamine or virtual entertainment.

I recently read Walter Isaacson’s biography of Leonardo daVinci. The biggest thing that struck me is that Leonardo was insatiably curious about EVERYTHING. He was a little boy in a man’s body.

In his journals, he posed questions like the following:

- Which nerve causes one eye’s movement to influence the other eye to move?

- Why are fish in the water swifter than birds in the air?

- How would you describe the tongue of a woodpecker?

People like Leonardo demonstrate that we need to become more childlike — not less. We need to embrace a newfound sense of wonder about the world.

When was the last time you gawked at the brilliant colors of fall leaves?

Stopped to watch two squirrels chase each other in your backyard?

Refused to use an umbrella so you could feel water droplets on your face?

Kneeled down on the sidewalk to watch a string of marching ants?

I’ve been trying to get better about putting on little kid goggles when I walk out my front door. I often stop my wife during our walks around the neighborhood to comment about fascinating cloud formations, trees, bugs, houses, and graffiti.

My goal is to actually see and appreciate what’s in front of me.

2.0 — Always be a student

“We live on an island surrounded by a sea of ignorance. As our island of knowledge grows, so does the shore of our ignorance.” -John Archibald Wheeler

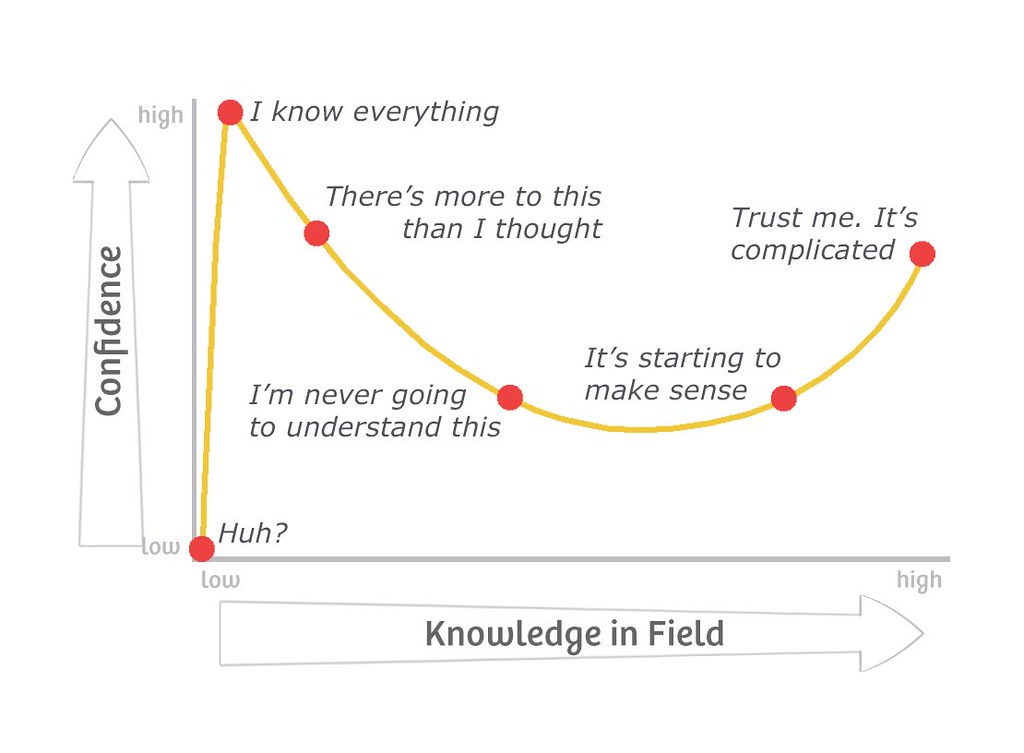

The Dunning-Kruger Effect is a cognitive bias that says people who don’t know much about a topic tend to overestimate their knowledge of the topic.

Confused? Let’s walk through a quick example.

Say I recently read an article about intersectionality. Now that I’ve read the article, I may think of myself as an expert on the topic. I may even be so proud of myself for reading the article that I find myself “teaching” others about intersectionality. In the 10 minutes it took me to read one post, I’ve gone from completely ignorant about the topic to completely informed. Magic!

Just like that, I’ve fallen prey to the Dunning-Kruger Effect.

From the perspective of our flawed human brains, our tiny bits of knowledge can seem really impressive. (To rip off the old motor vehicle safety warning, “Beware: Knowledge in brain is much smaller than it appears.”)

The incredible thing about knowledge is that it can sometimes have a humbling effect: the more you learn, the more you realize there is to learn.

That’s one reason why learning is so important to me: it exposes my ignorance.

2.1 — Drink deeply from good books

“What you will become in five years will be determined by what you read and who you associate with.” -Charles ‘Tremendous’ Jones

I cribbed this principle from renowned college basketball coach John Wooden, who cribbed it from his dad. (The best ideas are always stolen ones.)

The best way I’ve found to learn new things is by reading. Books have prompted me to become more curious about the world, ask deeper life questions, develop empathy for others, and make connections between diverse topics.

There are few things in life more important to me than reading, but I didn’t always feel that way. Junior high and high school bashed my love of reading out of me. I became focused on checking the box and getting the grade rather than enjoying literature and using it to inform my life.

For years during my teenage years, I didn’t read a single book for pleasure. Then, on a whim, I picked up Malcolm Gladwell’s book Blink during my senior year of college. That book reminded me that reading could be fun as well as educational, and I haven’t stopped reading since.

I now carve out 2–3 hours every night for reading. Despite the fact that I’m not a fast reader, I’m able to enjoy over 70 books per year solely due to the amount of time I spend reading. I’ll never give up the habit.

2.2 — Exhibit confident humility

“You have to be humble, and you can’t pretend to be someone you’re not or to know something you don’t…You have to ask the questions you need to ask, admit without apology what you don’t understand, and do the work to learn what you need to learn as quickly as you can. There’s nothing less confidence-inspiring than a person faking a knowledge they don’t possess. True authority and true leadership come from knowing who you are and not pretending to be anything else.” -Bob Iger

One of the most popular pieces of advice I heard in my 20s was “Fake it ’til you make it.” Friends, authors, and business icons all shared the same advice, so I figured it must be sound.

Then I realized something. I could tell when others around me were “faking it” with their overconfident bluster in meetings, unbridled optimism about strategic plans, and questionable decisions on company projects.

I wondered, “If I can tell they’re faking it, won’t people be able to tell when I’m faking it too?” (Answer: Yes.)

I now know that the strongest leaders are those who occasionally admit uncertainty — not those who blindly choose a path with bravado and chutzpah. Great leaders avoid the extremes of arrogance (unbridled confidence) and passivity (unbridled humility).

In short, the best leaders exhibit confident humility.

Confident humility is having the modesty to understand whether you’re the best person to make a decision. It means learning from others when they’re the expert and acting with boldness when you’re the expert.

Now, when I accept a new role or tackle a new project that’s a stretch for my skillset, I try to approach it from a perspective of confident humility.

2.3 — Assess yourself with 3rd-party objectivity

“If anyone can prove and show to me that I think and act in error, I will gladly change it — for I seek the truth, by which no one has ever been harmed. The one who is harmed is the one who abides in deceit and ignorance.” -Marcus Aurelius

Receiving feedback is tough, and cognitive dissonance is real.

Each of us is the hero of our own story, and when we hear something that goes against our inflated opinion of ourselves, it’s tough to know what to believe. We subconsciously choose to either stick with our warped perspective of ourselves or we completely lose our self-confidence.

Here’s what that looks like:

Belief: I’m a good employee.

But Then: My boss tells me I did a poor job on ABC project.

Cognitive Dissonance: I’m pretty sure that I’m an awesome employee, so that person must be wrong. Or perhaps I’m actually a bad employee.

Reality: I’m a hard-working person who makes mistakes.

Belief: I’m a loving husband.

But then: My wife is frustrated because I haven’t been listening to her.

Cognitive Dissonance: Gosh, I must be a horrible husband. Or maybe she’s wrong and she’s just taking out her tough day on me.

Reality: I love my wife and I sometimes struggle to be a good listener.

When we hear disconfirming feedback, instead of opting for the (probably accurate) gray area, we choose either A or B: We’re either awesome or horrible.

A truly grounded person would be able to view the situation from the perspective of a disengaged third party. So that’s become my goal. I want to essentially be able to watch myself from the sidelines: sitting in the bleachers, not wearing the jersey of either team.

I want to become a neutral third party with a bird’s-eye view of what happened, then act with self-reflection and humility to correct my own mistakes.

3.0 — Choose to never have a bad day

“Most people are about as happy as they make up their minds to be.” -Abraham Lincoln

When I was 17, I had the opportunity to join a citywide leadership course that included 15–20 community leaders. The course offered a peek behind the curtain of how a city is run: state government, municipal departments, the police and fire departments, local banking institutions, etc.

I learned a lot of interesting things during the course, but the biggest lesson came during an unlikely section: an icebreaker activity.

During the icebreaker, I met two community leaders: “Greg” and “Nancy.” Greg was a community banker who complained about all of the detailed paperwork he had to complete in his job. Within my first minute of meeting Greg, I learned about five aspects of community banking that he disliked. I left the interaction thinking, “Wow, banking must suck. I will never go into a profession like that.”

But then I met “Nancy.” Nancy raved about her job. She got to help little kids open their first savings accounts, 20-somethings buy their first homes, and middle-agers save for their retirement. Her profession? The same job as Greg. They even had the exact same job title.

My 17-year-old brain was horribly confused. Didn’t these two people have the same job? How could Greg’s experience be so different than Nancy’s?

Then I realized my mistake. They had the same job, but they brought vastly different perspectives to their jobs.

Nancy was building the community. Greg was pushing papers.

Nancy’s work brought her meaning. Greg’s brought him melancholy.

Nancy had a purpose. Greg had a paycheck.

Much later, I learned the famous Quarry Worker’s Creed: “We who cut mere stones must always be envisioning cathedrals.” I have no doubt that as Nancy filed the same boring ‘ol paperwork that Greg filed every day, she was envisioning someone crossing the threshold of their first house.

My experience meeting Greg and Nancy taught me a valuable lesson: each day, I get to choose whether I want to have a good day or a bad one.

Sure, on any given day, really shitty things may happen to me. I may break my finger, lose my job, grieve a lost family member, or deal with a difficult co-worker (all of which have happened to me in the past year).

But at the end of the day, I get the choice of how I want to view that day.

As one of my life rules, I’ve chosen to never have a bad day. I’ve decided to seek out the light amidst the darkness and the tenderness amidst the torment.

Now, I acknowledge that the world isn’t as simple as I’ve made it sound. Mental health issues like depression and anxiety are painfully real. There are chemical and biological factors that can bully their way into our lives and eliminate our ability to choose optimism or pessimism.

But I also know that there are a lot of Gregs in the world, and whenever I do get the choice, I’ll pick Nancy’s perspective every day of the week.

3.1 — Love all seven days

“You’re living for the weekend. I’m living for the week.” -Unknown

“Thank God it’s Friday.” Thousands of people across the country utter that phrase every week. And while I totally understand the sentiment (I love weekends too), that phrase says a lot about our society’s perspective on work.

The societal assumption is that we have to pay the piper five days (at least) in order to earn two days of freedom (at most). But I prefer to not view my weeks like that. I want to love all seven days.

That mindset means that I prioritize two things.

First, I try to redeem every day with something that gives me pleasure. That means that even if I’m traveling for work and I finish my client meetings and business dinners at 11 pm, I stay up to do something for myself. I’ll watch a short tv show, read a book, or go on a late-night walk—something to prove to myself that at least one aspect of that day was mine and didn’t belong to anyone else. For you, redeeming the day could mean getting a few minutes of playtime with your kids, going on an early morning run, or meditating for 10 minutes before bed. Whatever you need to do to label part of that day your own.

And second, I place a heavy emphasis on finding work that I enjoy. How big of an emphasis? Well, in the past decade, I’ve left two jobs without having another job lined up. Both times, it was scary to leave. I didn’t know what I would do next, and it’s difficult to deal with the uncertainty of not knowing where the next paycheck will come from. But those companies no longer felt like the right place for me to be — either due to the work culture or the type of work I was doing.

Although I don’t subscribe to the “passion mindset” that says every person needs to find work they’re passionate about, I believe it’s important to enjoy aspects of your work, to feel like you’re learning and growing, and to feel like your values align with the senior leaders of the company.

3.2 — Be hyper-present

“Don’t rush through the experiences and circumstances that have the most capacity to transform you.” -Rob Bell

On a recent neighborhood walk, I strolled past a Japanese restaurant. I love people-watching, so naturally, I looked through the window as I walked past.

Two girls were seated at a table across from each other. Both were on their phones, making zero eye contact.

At another table sat a young man and woman in their twenties. The man was on his phone — completely disengaged. As he scrolled away on his device, the woman looked expectantly at him, hoping he’d find her interesting enough to engage in conversation.

Two tables, one shared story: disengagement.

I wondered what was going on at each table. What was the story for each of these couples?

Friends swapping stories over a nice meal?

Siblings grabbing a bite to eat to catch up on life?

Lovers on their first date? 100th date?

In which of those situations would this level of disengagement be acceptable?

Is it ever okay?

I noticed the same behavior two years ago when my wife and I vacationed in Hawaii. There we were, in the most picturesque setting in the world, and half of the people around the pool were on their phones (pictured below). I couldn’t believe it.

Unfortunately, we live in a world of hyperactivity. We’ve lost the ability to slow down and forgotten how to be present. We’ve decided it’s a good bargain to trade real-world connection for dopamine-laden likes and retweets.

I refuse to make that trade. Even though it’s difficult, I want to be 100 percent present in every interaction.

4.0 — Control what you can control

“It is not what happens to you, but how you react that matters.” -Epictetus

The past few years, I’ve read a lot of Stoic philosophy. The biggest thing I’ve taken away from reading the Stoics is the importance of focusing on what you can control and forgetting about what you can’t control.

For example, as a writer, I control my influences, my work ethic, the time I’m willing to invest in a story, and the intensity of my editing process.

But once I’ve published a story, I have ZERO control over what happens. That is simultaneously refreshing and horrifying.

Here’s a list of a few things I can’t control with my writing: how many people read what I’ve written, what they think about what I wrote, whether and how they comment on my stories, how many times they re-share my post, whether my piece gets syndicated by a large publication, how much money I make from the story, whether an agent stumbles upon that story, etc. etc. etc.

There is a litany of things I cannot control. Once I hit “publish,” my work becomes the property of each reader. They choose what happens to it. And that’s okay.

As I’ve become more comfortable with this reality, I’ve enjoyed writing more. My goal is to trust the process and pay attention to my work — not its reception.

This goal carries over to many other aspects of my life as well. It used to devastate me when a boss or colleague didn’t like something I produced, but this “control what you can control” principle refocuses me on what is most important: Did I try my best? Did I act with integrity? Am I proud of my input, regardless of the subjectivity of the output?

4.1 — Look at the safe water while paddling

“He who indulges empty fears earns himself real fears.” -Seneca

I once read that if you’re trying to avoid dangerous rapids while paddling a kayak, you’re less likely to capsize if you focus on the calm water you’re trying to reach than if you focus on the rough waves. Looking at the rapids will make you more likely to wipe out. I have no idea if that advice is true, but I love the analogy, and I try to remember it anytime I’m feeling anxious.

For example, a couple of months ago, I was preparing for a client meeting. I began thinking about all of the things that could go wrong in the meeting: I could forget a key point I needed to share, I could botch the demo, etc. After a few minutes of anxious thoughts, I reminded myself that I was thinking about the rough water — and the very act of thinking about the rapids would make me more likely to hit them.

So I instead began picturing the smooth water: how much I had prepared for this moment, what I would feel like after I nailed the demo, how I would rise to the occasion and remember all of my key points. I was ready for this.

Our focus pre-determines our results. By focusing on the positive outcome, we make it more likely to come to fruition.

4.2 — No bad beats. Focus on the process.

“All events are neutral, and I can choose how to react to them. I can choose to be a victim to my circumstances, or I can choose to stand responsible for how I handle my circumstances.” -Daniel Negreanu

I’ve never been an amazing poker player, but the game fascinates me and offers many great analogies for life. Hang around a poker table long enough and you’ll hear someone complaining about a “bad beat” — slang for when a player loses a hand that they statistically thought they would win.

I too used to get frustrated in these situations. Whether you’re playing for big bucks at a casino or a few dollars with friends, it’s annoying to watch a good hand vaporize as the cards turn against you. But that’s just how it goes.

Games like poker expose a universal truth about life: sometimes, you can do everything possible in your power to “win” but things still don’t go your way.

In fact, it’s a mathematical certainty. If you’re holding cards that will win 95 percent of the time and you play that same hand 20 times, you’re bound to lose one of those hands.

This logic carries over to other aspects of life. Poker reminds me that sometimes I’ll do everything the best way I know how, and I’ll still lose. And that’s okay. The key is to focus on the process: Did I make the best decision I could with the information I had at the time? Did I adequately prepare?

If the answer to those questions is yes, I try to reconcile myself to the outcome, regardless of what happened. No bad beats.

5.0 — Use fear as a compass

“The bigger your comfort zone, the smaller your life.” -Jamie Jackson

One of my favorite books is Tribe of Mentors by Tim Ferriss. The book contains insights from over 100 successful people in fields as diverse as music, athletics, business, and film.

When I read that book, I learned that one of the biggest things that separates top performers from others is the way they view stress and fear. For example, here’s what performance psychologist Jim Loehr had to say:

“Protection from stress serves only to erode my capacity [to handle it]. Stress exposure is the stimulus for all growth, and growth actually occurs during episodes of recovery. Avoiding stress, I have learned, will never provide the capacity that life demands of me…In a real sense, to grow in life, I must be a seeker of stress.”

This reframing is a game-changer. It flips the script of the normal stress response (i.e., see something that scares you, turn the other way, avoid the fear).

Instead, the process becomes: see something that scares you, turn toward it, grow and learn. Stress leads to discomfort, which prompts change, which spurs growth, which results in success.

The things that most scare us are often the things we most need to pursue. Applying for a nerve-wracking promotion. Breaking up with a partner who has been psychologically (or physically) abusive. Coming out to friends and family. Volunteering to give a presentation in front of 200 people.

These things are scary as fuck. But in each situation, fear points the path to growth, success, and fulfillment.

5.1 — Run toward the fire

“You get paid in direct proportion to the difficulty of the problems you solve.” -Elon Musk

Five years ago, my boss Scott told me something I’ll never forget.

He said the best way to succeed in any job is to solve the gnarliest problems: “If you solve tough problems, you’ll inevitably be given more responsibility and move into a higher position. And you know what you’ll be rewarded with in that next position? Even tougher problems to solve.”

His advice was to “run toward the fire.” Look for the types of projects that other people say are too hard or too scary, then volunteer for those projects. Become known as the type of person who can solve the most difficult problems and you’ll never find yourself without a job.

Scott’s advice shifted my perspective. Rather than volunteering for tasks that were in my strike zone, I began taking on projects that were a true test of my abilities: the types of projects that I truly didn’t know if I could accomplish.

My willingness to raise my hand for those projects led to a greater number of mistakes but also a greater ability to learn new things.

5.2 — Choose dreams that scare you

“The size of your dreams must always exceed your current capacity to achieve them. If your dreams do not scare you, they are not big enough.” -Ellen Johnson Sirleaf

Five years ago, if you asked me what I wanted to do in my career, you would have gotten a very different answer than the one I give today.

For a long time, the answer inside my heart has been “I want to be a leadership author and speaker.” But that answer seemed too unrealistic…too BIG. I had barely admitted that dream to myself, yet alone to others.

So I settled for smaller, socially palatable answers like “I’m not sure. I just want to keep working my way up the corporate ladder” or — if I was feeling bold — “I want to become an executive of a Fortune 500 company.”

Those dreams are fine, but they weren’t my dream. My real dream scared me, and I thought it might scare others too. They might view it as arrogant, overly optimistic, or attention-seeking.

Then I stumbled across quotes like the one from Ellen Johnson Sirleaf (above) and this one from Benjamin Hardy: “If what you’re pursuing right now isn’t so big that you’d be embarrassed to share it with most of the people in your life, I challenge you to take a step back and really think about it.”

The only people who achieve stratospheric goals are those who have stratospheric dreams. The challenge is that we must simultaneously live in the stratosphere (dreaming of what is possible) while also keeping our feet planted on the ground (executing the daily work).

6.0 — Be both candid and kind

“One of the most important insights anyone in business can have is that it’s not cruel to tell people the truth respectfully and honestly.” -Patty McCord

A few weeks after starting my first job out of grad school, my district manager told me I’d probably need to fire one of my team leads (“Jerry”) who reported to me. I asked why Jerry needed to be fired and why no one had done it yet.

“All of Jerry’s past managers have been scared of him,” the district manager said. “He’s a burly football player and he doesn’t take feedback well. But he’s been causing a lot of problems and he’ll need to go if he doesn’t shape up.”

Wowza. Talk about getting a pile of shit dropped in your lap.

I spent the next couple of months trying to work with Jerry and give him loads of feedback. But unfortunately, it was too little, too late. After five years of working at the company and receiving limited feedback, Jerry had convinced himself that he was the bee’s knees and had no issues to fix. He thought I was the problem — not him.

So the day came that I had to fire Jerry, and our security guard had to practically drag Jerry out of the building as he yelled obscenities at his (now former) co-workers.

The experience was rough on Jerry and also on me. But it taught me a very important lesson: it’s more kind to share feedback than to withhold it.

Other managers had “protected” Jerry (and themselves) by refusing to share feedback. And their lack of courage ultimately cost Jerry his job. He wasn’t a bad guy. Just like anyone else, he took pride in his work and wanted to do good work, but he wasn’t given the chance to encounter his issues head-on until it was too late.

Many people mistakenly think you must choose to be either candid or kind. They think you can either: (A) share a tough message and lose the relationship or (B) stay silent and maintain the relationship.

The authors of Crucial Conversations call this false dichotomy a “sucker’s choice.” The truth is that we don’t have to choose. It’s possible to share candid feedback in a kind, caring way.

6.1 — Seek common ground

“Don’t worry about accepting or rejecting the other person’s story. First work to understand it. The mere act of understanding someone else’s story doesn’t require you to give up your own.” -Douglas Stone, Bruce Patton, and Sheila Heen

In tough conversations, it’s important to lead with facts and mutual agreement rather than arguments for your side. This is true whether you’re sharing feedback, debating politics, or arguing with a family member.

I’ve learned to open the conversation with what both parties know to be true. Establish common ground.

If you’re debating abortion, the common ground might be that you both value human life (one of you is focused on the child, while the other is focused on the mother). If you’re arguing about unemployment benefits, you likely both agree that you don’t want to incentivize people not to work. In every conversation, there is common ground. We just need to find it.

Beginning with mutual agreement sets a positive tone for the rest of the conversation. If I’m looking for places where we agree, then chances are good that you’ll begin to do the same. Common ground is the cornerstone of productive disagreement.

6.2 — Be efficient with processes and effective with people

“Efficiency is doing things right; effectiveness is doing the right things.” -Peter Drucker

I am a maniac for efficiency. I sometimes even lay in bed thinking about the fastest route I can take to get from point A to B to C while I’m running errands. It’s weird, but it all comes back to my desire to not waste a single moment of time. Time is precious, and I want to spend mine wisely.

But being hard-wired for efficiency can have its drawbacks. Several years ago, I realized that I was treating my interactions with coworkers as little more than business transactions. I had been jumping from one conversation to another as fast as possible, donning my corporate crusader cape to solve as many business problems as possible. Along the way, I commoditized my relationships with my colleagues. They didn’t feel valued or heard.

Thankfully, I stumbled on Peter Drucker’s book The Effective Executive. While reading Drucker’s insights about the difference between efficiency and effectiveness, I realized that I had let efficiency dominate my life.

What I needed to do was separate the way I thought about processes and the way I thought about people. Processes can (and should) be streamlined for efficiency. People shouldn’t.

Efficiency is the absolute WRONG way to think about interactions with other humans. People need to be cared for, loved, appreciated, and respected — all of which take time.

My new goal is to be efficient with processes and effective with people.

7.0 — Simplify

“If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough.” -Einstein

Five years ago, I worked for an investment accounting company. As an MBA grad, I already knew the basics of stocks and bonds, but there was still a TON I needed to learn about the world of investment accounting.

My first week on the job was packed with training sessions, and one of the main concepts I was supposed to learn that week was an esoteric but important concept called bond amortization.

I spent a full hour locked in a room with the firm’s lead accountant as he white-boarded formulas and explained the nitty-gritty details of amortization. At the end of the session, I still had no fucking clue what amortization was. I felt like a complete idiot and questioned whether I’d succeed at the company.

Thankfully, I was able to snag a few minutes with another accountant later that week. In ten minutes, she taught me everything I needed to know about amortization. As relief swept over me, I realized that I wasn’t the problem. The teaching style had been the problem.

The first trainer rushed me over to the deep end of the pool and made me jump off the high dive before I even knew how to swim.

The second trainer held my hand in the shallow end of the pool where I could take a few baby steps and get my feet wet. Rather than immediately diving into granular details, she began with the basics and inched me toward understanding. She chunked the information into manageable concepts, used simple terminology, and drew upon my existing knowledge to build connections to the new topics I had to learn.

That experience influenced the way I think about many things in life, including public speaking, tackling complex projects, and teaching others.

I’ve learned that true expertise isn’t spouting off long words and complex jargon; it’s using simple words to convey powerful ideas.

7.1 — Relentlessly single-task

“If you try and chase two rabbits, you will not catch either one.” -Russian proverb

Have you ever walked over to a colleague’s desk (or virtual Zoom screen) to review something, and they had to weed through 100 browser tabs to find the one that contained the spreadsheet or email they wanted to show you?

Situations like that drive me nuts because they’re living proof of the multi-tasking myth. Each of us wants to believe that we can do 100 things at once, but we can’t. The more tasks we try to tackle simultaneously, the worse we perform on each one.

The human brain has a limited amount of bandwidth, and how we spend that bandwidth matters.

The best way to maximize productivity and focus is to eliminate the endless clutter that stands between us and our most important tasks. That means fewer browser tabs, less multi-tasking, and no (or limited) slack messaging during meetings and Zoom calls.

Ever since reading Cal Newport’s productivity treatise Deep Work, I’ve become a relentless single-tasker. I even took that mindset to an extreme during COVID by refusing to bring computer monitors home with me. After years of working from at least two screens, I’m now working off one small laptop screen. And I love it. Whatever is on my ONE screen receives my entire focus.

7.2 — Identify the first step

“Far too often, we don’t start because we can’t get our minds around the entire thing. We don’t take the first step because we can’t figure out the seventeenth step. But you don’t have to know the seventeenth step. You only have to know the first step. Because the first step is always 1. Start with 1.” -Rob Bell

Seven years ago, I received one of the best compliments of my career. I was working as a Product Owner of a software company, and the director of our department told me, “You do a great job of subdividing big projects into manageable chunks. That will serve you well in your career.”

Before he said that, I hadn’t realized the importance of that skill.

His comment prompted me to self-reflect. Sure enough, as I thought back to the beginning of each big project our team had tackled, I remembered my colleagues (and me too!) sometimes feeling overwhelmed as we scoped future projects. That year, we had rewritten two core aspects of our software platform — projects that lasted for months.

Any project of that scope is daunting, so I had always focused the team on the first step: What do we do TODAY? What do we prioritize THIS WEEK?

I try to apply that same mentality to daunting projects today, like when I began writing my first book and when I implemented new software systems for my company.

The key is to identify the first step. Then begin walking in that direction.

What is YOUR operating manual for life?

I will continue refining these rules for the rest of my life. In a world of a million distractions, these rules remind me what’s most important.

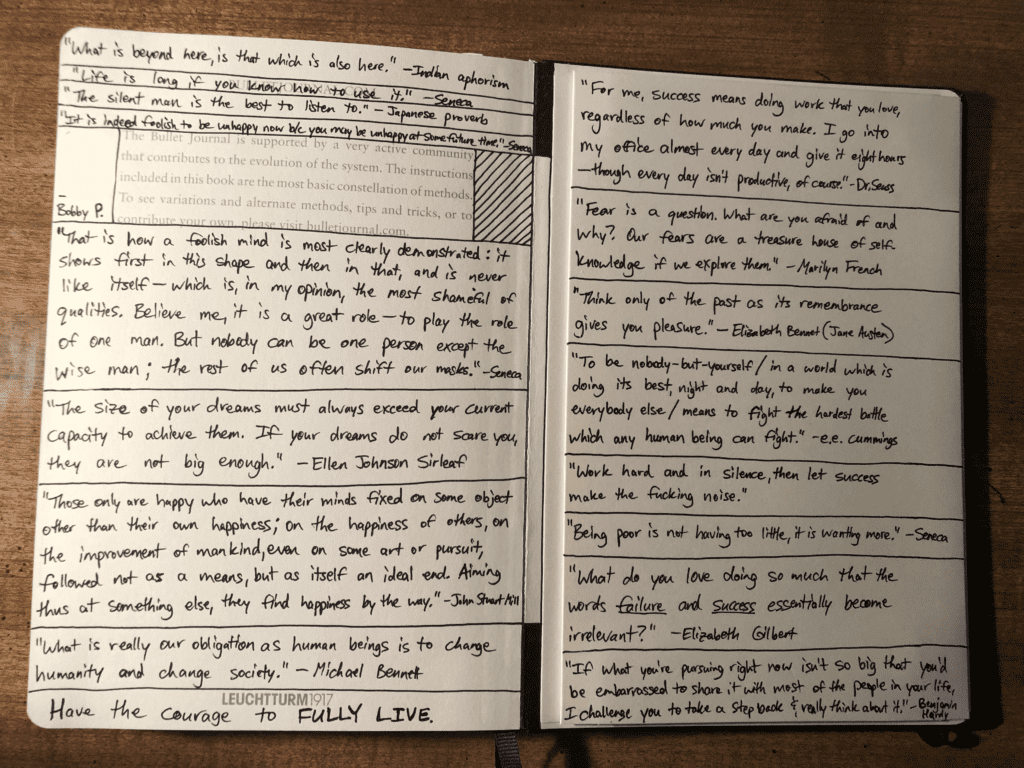

I absolutely don’t live out these principles perfectly (or even adequately) all of the time. Some of the rules are on this list because I struggle with them. I need to be reminded, so I write these rules inside every one of my journals.

The two rules I struggle with the most are “Control what you can control” and “Use fear as a compass.” I often get anxious about factors outside my control, which is why I read so many Stoic philosophy texts and self-help books. And yes, I still struggle to run toward fear. I’ve been trying to improve in that area by raising my hand for difficult projects, but it’s a daily battle.

But as I mentioned at the start of this post, every person must create their own operating manual for life. I hope that a few of my principles will resonate with you, but your principles should look very different than mine.

If you want to begin crystallizing your own rules for living, I encourage you to start the same way I did:

- Read biographies and memoirs about people you admire. Pay attention to what traits made them successful and what traits you want to emulate.

- Begin journaling. Jot down phrases, quotes, and ideas that jump out to you.

- Think about the 5–10 biggest life events that shaped who you are as a person. What made those events so important? What did they teach you? What values or principles carried you through your toughest times?

- Gradually, begin writing your own list of personal rules to guide your actions. Refine the list over time.

- Brainstorm ways to remind yourself of your rules. Write them on sticky notes on your desk or bathroom mirror, print and laminate a small card that you can carry with you, or write them in the front of your journal.

Humans don’t come with an operating manual. You have to create your own. I hope you’ll invest enough time in yourself to create one.