Book Review: “Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise”

Book: Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise by Anders Ericsson and Robert Pool

Reviewer: Bobby Powers

My Thoughts: 9 of 10

Ever heard of the 10,000-hour rule? It was popularized by Malcolm Gladwell in his book Outliers. Gladwell based that rule on the research of Anders Ericsson, who just released his own book that sets the record straight on what exactly is required to become an expert in a given field. The 10,000-hour rule isn't quite true (read Peak to find out why), but it does get a few things right—namely that talent is overrated and hard work rules the day. Ericsson shares research conducted on chess grandmasters, violinists, musicians, ballerinas, and others at the top of the world in their craft. The research conclusively shows that deliberate practice trumps innate talent in the battle for the podium in any given area of expertise. Peak is an amazing book that has practical implications spanning education, sports, and personal drive to be the best in whatever you love to do.

Takeaways from the Book

Expertise Takes Hard Work

- “We now understand that there’s no such thing as a predefined ability. The brain is adaptable, and training can create skills that did not exist before...Learning isn’t a way of reaching one’s potential but rather a way of developing it. We can create our own potential.”

- “I can report with confidence that I have never found a convincing case for anyone developing extraordinary abilities without intense, extended practice.”

- “When people say God blessed me with a beautiful jump shot it really pisses me off. I tell those people, ‘Don’t undermine the work I’ve put in every day.’ Not some days. Every day. Ask anyone who has been on a team with me who shoots the most. Go back to Seattle and Milwaukee, and ask them. The answer is me.” -Ray Allen, 10-time NBA all-star and greatest three-point shooter in the history of the league

- “People do not stop learning and improving because they have reached some innate limits on their performance; they stop learning and improving because, for whatever reasons, they stopped practicing—or never started. There is no evidence that any otherwise normal people are born without the innate talent to sing or do math or perform any other skill.”

Mental Representations

- A mental representation is a brain schema/shortcut developed through deep experience and practice. “Any relatively complicated activity requires holding more information in our heads than short-term memory allows, so we are always building mental representations of one sort or another without even being aware of it.”

- “The thing all mental representations have in common is that they make it possible to process large amounts of information quickly, despite the limitations of short-term memory.”

- “The main thing that sets experts apart from the rest of us is that their years of practice have changed the neural circuitry in their brains to produce highly specialized mental representations, which in turn make possible the incredible memory, pattern recognition, problem solving, and other sorts of advanced abilities needed to excel in their particular specialties.”

- “The main purpose of deliberate practice is to develop effective mental representations.”

- “In any area, not just musical performance, the relationship between skill and mental representations is a virtuous circle: the more skilled you become, the better your mental representations are, and the better your mental representations are, the more effectively you can practice to hone your skill.”

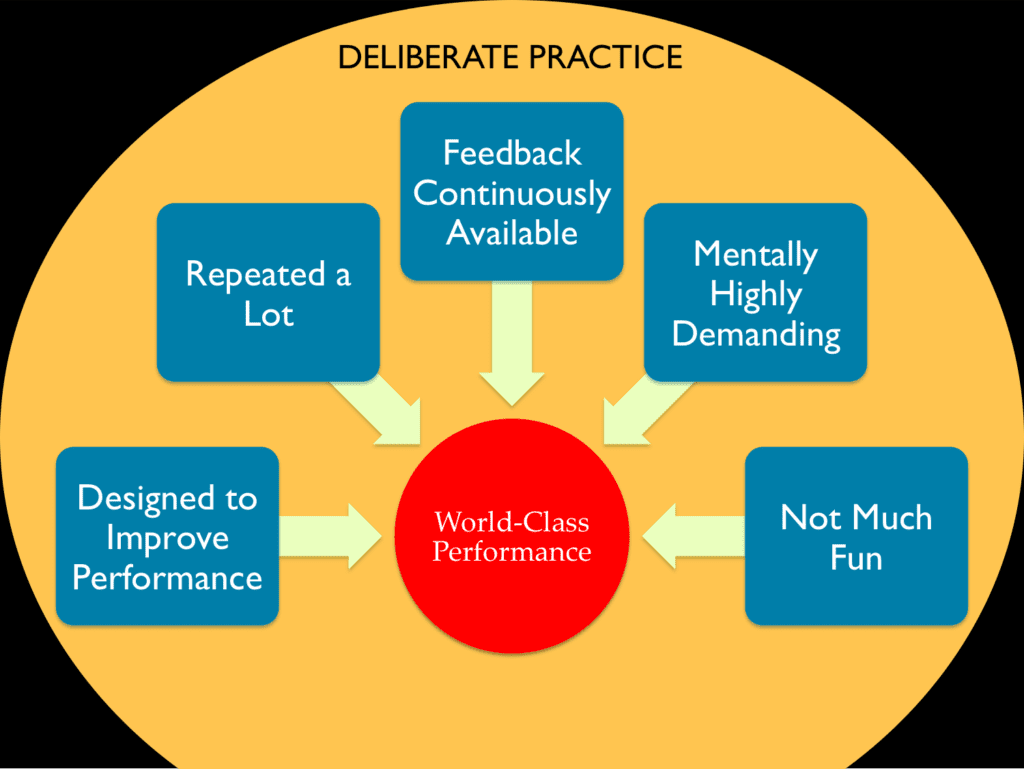

Deliberate Practice

- “Deliberate practice is purposeful practice that knows where it is going and how to get there.”

- “Deliberate practice takes place outside one’s comfort zone and requires a student to constantly try things that are just beyond his or her current abilities. Thus it demands near-maximal effort, which is generally not enjoyable.”

- “Doing the same thing over and over again in exactly the same way is not a recipe for improvement; it is a recipe for stagnation and gradual decline.”

- Key aspects of deliberate practice:

- Requires a teacher who can provide specific practice activities

- Involves well-defined, specific goals (not aimed at some vague overall improvement)

- Requires a person’s full attention and conscious actions

- Involves feedback and modification of efforts in response to that feedback

- Produces and depends upon effective mental representations

- Systematically works to improve micro-aspects of each skill

- “Remember: if your mind is wandering or you’re relaxed and just having fun, you probably won’t improve.”

- “The hallmark of purposeful or deliberate practice is that you try to do something you cannot do—that takes you out of your comfort zone—and that you practice it over and over again, focusing on exactly how you are doing it, where you are falling short, and how you can get better.”

Other Insights

- “When people assume that talent plays a major, even determining, role in how accomplished a person can become, that assumption points one toward certain decisions and actions. If you assume that people who are not innately gifted are never going to be good at something, then the children who don’t excel at something right away are encouraged to try something else...The prophecy becomes self-fulfilling.”

- “Since the 1990s brain researchers have come to realize that the brain—even the adult brain—is far more adaptable than anyone ever imagined, and this gives us a tremendous amount of control over what our brains are able to do."

- “This is how the body’s desire for homeostasis can be harnessed to drive changes: push it hard enough and for long enough, and it will respond by changing in ways that make that push easier to do.”

- “Once you have identified an expert, identify what this person does differently from others that could explain the superior performance.”

- “To date, we have found no limitations to the improvements that can be made with particular types of practice.”

- “The creative, the restless, and the driven are not content with the status quo, and they look for ways to move forward, to do things that others have not. And once a pathfinder shows how something can be done, others can learn the technique and follow. Even if the pathfinder doesn’t share the particular technique...simply knowing that something is possible drives others to figure it out.”

- “I suspect that such genetic differences—if they exist—are most likely to manifest themselves through the necessary practice and efforts that go into developing a skill. Perhaps, for example, some children are born with a suite of genes that cause them to get more pleasure from drawing or from making music. Then those children will be more likely to draw or to make music than other children. If they’re put in art classes or music classes, they’re likely to spend more time practicing because it is more fun for them. They carry their sketchpads or guitars with them wherever they go. And over time these children will become better artists or better musicians than their peers--not because they are innately more talented in the sense that they have some genes for musical or artistic ability, but because something—perhaps genetic—pushed them to practice and thus develop their skills to a greater degree than their peers."

Think you’d like this book?

Other books you may enjoy:

- Mindset by Carol Dweck

- Grit by Angela Duckworth

- The Talent Code by Daniel Coyle

- Talent is Overrated by Geoff Colvin

Other notable books by the authors:

- Toward a General Theory of Expertise edited by Anders Ericsson and Jacqui Smith

- Beyond Engineering: How Society Shapes Technology by Robert Pool

Want to become a stronger leader?

Sign up to get my exclusive

10-page guide for leaders and learners.