Book Review: “Crucial Conversations”

Book: Crucial Conversations by Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, Ron McMillan, and Al Switzler

Reviewer: Bobby Powers

My Thoughts: 10 of 10

I don't re-read books often, but I made an exception for this one. I've now read it three times, and I plan to revisit this book for the rest of my life. It's honestly that good. Crucial Conversations is packed with insights into how to deliver a tough message. The most valuable lesson I learned was the tendency of the human brain to craft biased hero/villain stories amid periods of conflict with others. I draw upon concepts from this book everyday in my interactions with my colleagues, spouse, and friends.

Takeaways from the Book

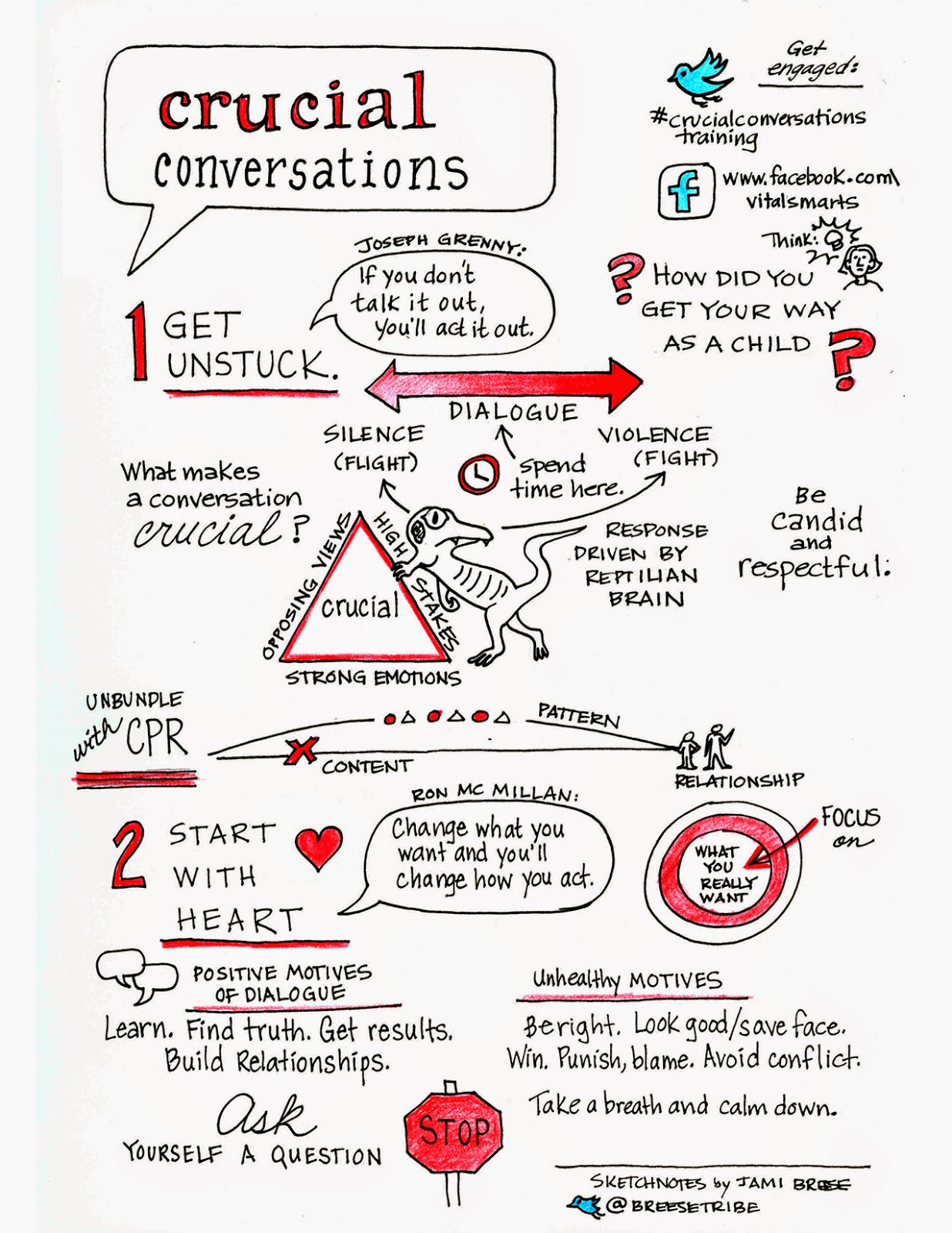

What is a "Crucial Conversation"?

- "When conversations matter most, we're usually at our worst."

- Crucial Conversation = A discussion between two or more people where...

- Stakes are high

- Opinions vary

- Emotions run strong

The Shared Pool of Meaning

- “When it comes to risky, controversial, and emotional conversations, skilled people find a way to get all relevant information (from themselves and others) out into the open.” They ask clarifying questions to encourage others to add their knowledge to the “shared pool.”

- Generating a shared pool of meaning has several advantages:

- “As individuals are exposed to more accurate and relevant information, they make better choices.”

- “When people purposefully withhold meaning from one another, individually smart people can do collectively stupid things.”

- When a decision is finally reached, everyone knows why/how you got there and can be committed to the final decision.

Work on Yourself Before Working on Others

- “Although it’s true that there are times when we are merely bystanders in life’s never-ending stream of head-on collisions, rarely are we completely innocent. More often than not, we do something to contribute to the problems we’re experiencing."

- “It’s the most talented, not the least talented, who are continually trying to improve their dialogue skills.”

- “The best at dialogue speak their minds completely and do it in a way that makes it safe for others to hear what they have to say and respond to it as well. They are both totally frank and completely respectful.”

Embrace “And” > “Or” When Making Decisions

- We often fall into the pitfall of making a “sucker’s choice” between two ugly options. Example: We think we need to choose between bringing up something important or being kind. We can have both.

- “What makes these sucker’s choices is that they’re always set up as the only two options available. It’s the worst kind of either/or thinking. The person making the choice never suggests there’s a third option that doesn’t call for unhealthy behavior. For example, maybe there’s a way to be honest and respectful. Perhaps we can express our candid opinion to our boss and be safe.”

*Note: Jenna Ryan on The Self Love U Blog has more amazing Crucial Conversations sketchnotes on her blog. Click on the link for her site or the image above to see more of her work.

Create a Safe Environment for Voicing Productive Conflict

- When put into challenging situations, people often resort to silence or violence. To counter this unproductive tendency, establish mutual purpose in conversations with others.

- “Mutual purpose means that others perceive that we are working toward a common outcome in the conversation, that we care about their goals, interests, and values.“

- Example: “Pro-life” advocates were asked to partner with “pro-choice” advocates to establish a mutual purpose between their two groups. Despite the fact that both sides had passionate opinions about abortion, they were collectively able to establish a mutual purpose of reducing teen pregnancies. This shared purpose aligned both sides behind a common goal—despite the fact that they vehemently disagreed with each other on many other issues.

- Use contrasting to rebuild safety when others misinterpret your intent in the discussion. Contrasting sets the boundaries of your message by expressing what you DO mean and what you DON’T mean.

- For instance, if one of your personable team members needed to work on their technical skills, contrasting could sound like this: Let me put this in perspective. I don't want you to think that you're not doing a good job as an Account Manager. You have incredible interpersonal skills and clients love working with you. I just think you could be even better if you worked on your technical proficiency. Strive to learn the details of our technical processes and you would be unstoppable.

Don’t Confuse Stories with Facts

- “Just after we observe what others do and just before we feel some emotion about it, we tell ourselves a story. That is, we add meaning to the action we observed."

- The Path to Action: See/Hear —> Tell a Story —> Feel —> Act

- We cannot help the fact that our brain instantly constructs a story based upon a set of observations. However, we can work to always put facts before interpretations (stories) and open our minds to other stories that fit the facts we’ve observed.

- Three story archetypes show up frequently in the mental stories we tell ourselves:

- Villain - Someone else is the "bad guy."

- Victim - We have been wronged.

- Helpless - We cannot do anything about it.

- We often turn others into villains by telling a bad story for them based on what we’ve observed. “When you find yourself labeling or otherwise vilifying others, stop and ask: 'Why would a reasonable, rational, and decent person do what this person is doing?'”

State the Path that Led to Your Story

- Example: "The cheating husband"

- The Facts: Carole reviews her and her husband Bob’s monthly credit card statement, only to find that there’s a charge from the "Good Night Motel"—a cheap place located not more than a mile from their home.

- Carol's Mental "Story": “‘Why would he stay in a motel so close to home?’ she wonders. ‘And why didn’t I know about it?’ Then it hits her—‘That unfaithful jerk!’”

- Other "Stories": What story did Carole tell herself? What other stories could be told from these facts?

- The Truth: “The couple had gone out to a Chinese restaurant earlier that month. The owner of the restaurant also owned the motel and used the same credit card imprinting machine at both establishments. Oops.”

- Sometimes it's important to share your story with someone during a disagreement. In those instances, it’s vitally important to first lay out the facts that led you to craft that story. Here’s why:

- Facts are the least controversial.

- Facts are the most persuasive.

- Facts are the least insulting.

- Facts contribute to the shared pool of meaning.

- Just like Carole, we jump to conclusions frequently. These conclusions are often fraught with unfair assumptions and inadequate facts. Be careful what story you tell. Take a second to ask clarifying questions and assume positive intent. You often don't have all the facts.

Think you’d like this book?

Other books you may enjoy:

- How to Win Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie

- Thanks for the Feedback by Douglas Stone and Sheila Heen

- Difficult Conversations by Douglas Stone, Sheila Heen, and Bruce Patton

Other notable books by the authors:

Want to become a stronger leader?

Sign up to get my exclusive

10-page guide for leaders and learners.